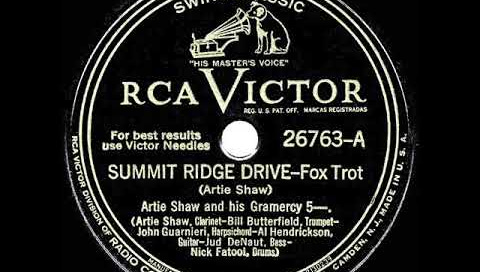

1940: Summit Ridge Drive - Artie Shaw and his Gramercy Five

For best results, use Victor Needles

Musicians are like magicians, or sorcerers and conjurers. They manipulate the air and bend and vibrate our atmosphere into the wonderful sounds that we can hear. Alongside the sight of a clear nights sky full of stars, the feeling of true love or watching an animal happily existing, what is more magical than that?

Some are, admittedly, better magicians than others. Some can perform simple tricks that dazzle an audience in the moment whilst others can perform feats that will transform your whole world.

In the pre-rock and roll era, bandleaders like Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller were the biggest magicians, and the true stars of their times. Even Sinatra took second billing as the featured vocalist on his first singles, first with Harry James as the big name act on the discs of songs like All or Nothing At All, It’s Funny to Everyone but Me and On a Little Street in Singapore, and then later behind the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra on songs such as Polkadots and Moonbeams, I’ll Be Seeing You, Imagination and East of the Sun (and West of the Moon).

Some of the bandleaders of the era were pure entertainers, happy and hoping to get a hall-full of young couples swinging and jiving or putting on a show across the radio waves. Artie Shaw was pitching for something a little more than that, and wanted to be thought of as an artist. No surprise, really, it was even in his name.

Shaw once said that “art happens when somebody with skill loves what he is doing and works at the absolute top level of his ability”, and a song like Summit Ridge Drive is what happens when you get six such somebodies with skill together, loving what they do and working to the absolute top level of their abilities.

Shaw wasn’t the first to carve a smaller band out of his main orchestra—Benny Goodman had played with a trio culled from a far bigger group from as early as 1935—but he was innovative in other ways with his own smaller ensemble, the Gramercy Five.

Way before The Beatles, The Kinks or Van Dyke Parks were incorporating baroque elements into their pop (actually, before most of them were even born), Artie Shaw was stirring it into his swing.

The harpsichord which makes Summit Ridge Drive so unique is supplied by John Guarnieri, and his playing with the Gramercy Five is notable for being the first time the instrument was used anywhere in a jazz recording. Guarnieri was better known as a ragtime or stride pianist, but Shaw had another vision for him in the group.

The other notable thing about this song is the rhythm, and the genre bending. It’s part jazz, part blues, part swing and all right. It’s a slow locomotive of a song, whistling along the tracks, through the hills and tunnels of an old, lost world. The imagined 1930s of the past flying by outside the window, and riding on in to the imagined 1940s to come. Never making a stop in its bid to get where its going, but also never in too much of a hurry to get there, either. Nick Fatool’s drums and Jud DeNaut’s upright bass drive the whole thing along. Chugging along percussively is Al Hendrickson on guitar, barely audible now, but he’s in there alongside Fatool and DeNaut in the driver's compartment, running the engine.

And there are a few detours along the way, too. At first, Shaw acts as the conductor with his clarinet, checking the tickets of the other musicians and keeping the tune in time, in check and the train on the tracks, but, as the song rolls along, he, alongside the harpsichord and Bill Butterfield on trumpet, derails the whole enterprise; forging a new path and a new sound and taking things out into a new frontier.

That second half of the song takes off in a whole new direction, and, despite the fact that this Gramercy Five feel more like one solid unit rather than six individual musicians, it can at times start to feel like there are two songs being played at once here. Those churning drums, bass and guitar never stray from their course for a moment and there is a wonderful tension between the simplicity of what they’re playing and the frenetic racing between Guarnieri’s harpsichord, Shaw’s clarinet and Butterfield’s trumpet.

The leads each pick up phrases and try them on, turn them inside out and toy with repetition or slight alterations on a theme. They lock in together and drift apart again. They’re dueling and competing and completing and complementing each other. They’re showing off to one another, to us listening on, and, to themselves. All the while, they are building up a head of steam that feels unsustainable.

Having taken a section in the spotlight each, this trio within the sextet become frantic, they become frenzied and manic. This runaway train is hurtling towards the edge of a cliff with each player now doing his best to outdo the others to get that final blaze of glory. When they lock in to the same riff it’s divine, and when they are playing off of each other there is a beautiful chaos. Just when you think the wheels are about to come off and the whole thing is about to crash and burn, they each hit the brakes and pull up to a perfectly executed stop. It might not have seemed like it, but just like the flying and singing brakeman Casey Jones, they were in control the whole time.

All of that from just six musicians and a little over three minutes? That’s not just art, that is real magic.