I’ve been thinking about A Complete Unknown a lot this week. So much of the film revolves around Dylan’s pivotal early Newport appearances, but one of my favourite scenes took place on a much smaller stage. Alongside Ed Norton’s wonderful Pete Seeger, Dylan jams a while with the bluesman Jesse Moffette. I didn’t know it until I left the cinema, but the fictional Moffette is played by the real-life son of none other than Muddy Waters, “Big Bill” Morganfield. It's no wonder he’s the best singer and musician in the movie!

He’s a fantastic figure in the film, and a fantastic blues singer and guitarist in his own right, as well, and has been releasing albums since the late 1990s. As well as writing, releasing and performing his own music, he has also helped revive the spirit of Muddy Waters, alongside his brother Mud Morganfield, in numerous stunning performances of his father’s songs through the years, like the one linked below. Listen to the insistent, crashing drumming on this, the fierce bite and stab in the famous guitar turnaround, the blues-busting harmonica and that earth-shaking Morganfield power. We don’t get music like this in England. I didn’t think they made music like this anywhere, anymore, but thank God they do. Lord knows we need it.

For anyone who somehow didn’t already know, A Complete Unknown makes it very clear how important his appearances at Newport Folk Festival were in Dylan’s early career. But he wasn’t the only one to have given seminal, career defining performances on those hallowed Rhode Island festival grounds.

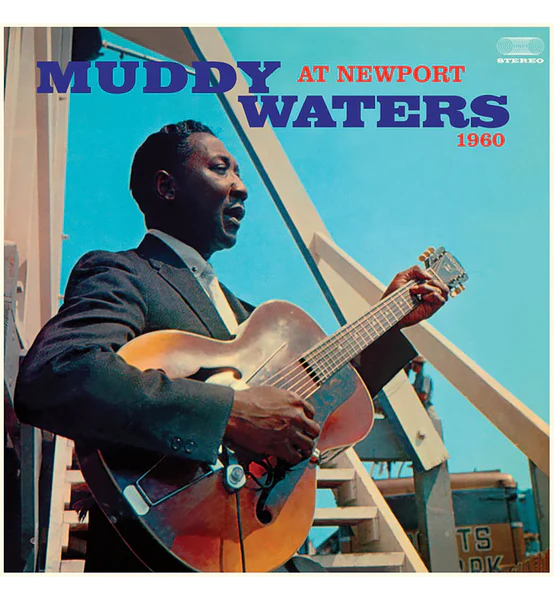

Muddy Waters had long since established himself as the father of the modern Chicago blues way before Dylan had even ever heard the name Robert Johnson. In fact, Muddy Waters was recorded singing for the first time in the same year that Dylan was busy being born, all the way back in 1941.

Under the remit of the Library of Congress, Alan Lomax (who appears as a character himself in James Mangold’s new movie) travelled to the Stovall Plantation in Mississippi in search of the legendary Robert Johnson. Little did he know, though, that Johnson had been laid low in mysterious circumstances some years previously, but not before leaving his mark on a young blues singer on the plantation named McKinley Morganfield, better known to the world under a name given to him by his grandmother, Muddy Waters.

Waters worked the land in the day and he worked the crowds at night, playing slide guitar, harmonica and singing his songs at cookouts, fish frys and juke-joints. It wasn’t until Lomax recorded him that he heard his own voice for the first time, though, and realised that he really had something and, man, the stuff he got will bust your brains out, baby. Lomax returned to record him on a few further occasions, but the confidence that hearing his own singing and playing played back that first time had inspired in the 28 year old bluesman a dream about life away from the plantation.

Before long, Muddy Waters had moved to Chicago, jumped from acoustic music to electric blues and revolutionised the face of the music scene he found himself in (sound familiar, A Complete Unknown fans?).

I think Muddy Waters is just about as cool as you can get. Those high cheekbones, the dismissive, laughing but sleepy eyes, his smirking mouth moved over to the side and accentuated with a pencil thin moustache, and his pomade quiff-hair give him the look; that earthy, resonant, gritty and gripping, powerful and sensuous voice gave him the sound, whilst his sharp suits gave him the style. No one has ever been badder or bigger or cooler or slicker than Mr Muddy Waters, and it also helped that he knew how to put the hottest band in town together, too. Whether it was Junior Wells, Big Walter Horton or James Cotton on harmonica, Willie Dixon on bass or Memphis Slim, Otis Spann or Pinetop Perkins at the keys, Muddy had the pick of the crop when it came to such phenomenal sidemen. Muddy was no slouch himself, and he could - and did - play a mean guitar with the very best of them.

In 1954, Elaine Lorillard founded the Newport Jazz Festival with her husband Louis, preceding its famous Folk sister-festival by a full five years. Billie Holiday took top billing at the first instalment, and the event continued to draw the biggest and best names in the genre like Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Louis Armstrong in the following years.

In 1960 Muddy Waters was booked to top the blues section of the show but the entire event was thrown into jeopardy in the days before he was due to play when a riot broke out at the festival site and threatened to get the whole event cancelled. The police responded with their characteristic calm and cool when Ray Charles’ audience became a little rough and rowdy by launching tear gas into the sea of bodies and bringing out their water hoses to calm the crowd. Thankfully, order was somehow restored and the show went on. Waters wowed the crowd for a little over 30 blistering, glistening, mind-blowing minutes during his Sunday show on July 3rd.

Backed by Otis Spann on piano, Pat Hare on guitar, James Cotton on harmonica, Andrew Stephens on bass and Francis Clay behind the drums - who had all also played behind John Lee Hooker and in a set fronted by Spann earlier in the day - Waters is at the top of his game throughout. His voice is so of the earth, so deeply rooted and deeply powerful that it fixes you to the spot when you stand with every note. He stills you and chills you and moves you all at once. He is so earthy, and yet so other-worldly. His band behind him play as if they are all an extension of the same brain, they're not individual band members but one unit, and they’re all pulling in the same direction, building up the perfect canvas on which Waters can lay down the lyrics to songs like I Got My Brand On You, I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man, Baby Please Don’t Go, Tiger In Your Tank and I Feel So Good.

He might be singing the blues, but these songs make you feel so good. They’re electric, they’re energising and they make you want to get up and move. Clay really swings on the drums, Cotton plays his harp like a runaway train, Otis Spann is a genius with the keys and Andrew Stephens really walks the floor with his bass. Between Pat Hare and Muddy Waters you don’t need any other guitarist, and then of course, Waters floods the whole space with his beautiful voice.

We are so lucky that Alan Lomax found and encouraged Muddy Waters when he did, that Phil and Leonard Chess continued to record him in Chicago, and that this show was captured and released on record, too.

And, even better than that, there is a video, as well.

Look at the energy on that stage when he sings his trademark I Got My Mojo Workin’. Look at that energy in the audience - and it’s worth noting that it’s a mixed audience at this pre-Civil Rights show having such a ball and being brought together by this music - when he does, and look at those moves of his! Matching the intensity of his vocals, Muddy Waters explodes into life and really gets up and gets down. At times here, he even puts Elvis Presley to shame with his gyrations and dancing. It’s a wonder he was allowed to be filmed below the waist.

At the end of the breathless performance, all of the day’s blues performers returned to the stage to join Waters and his band for a medley of blues standards, and closed with a new poem-as-song, Goodbye Newport Blues, written by festival director Langston Hughes in response to the earlier police trouble at the event. Otis Spann took the lead vocal, as Muddy Waters had exhausted himself too much to sing any more during his showstopping main set.

Every one of those men on stage was a master at their instrument. Each one was a master when working together and when working a crowd and they were all masters in putting the song over. Muddy Waters knew how to pick the best bands because he was himself the best front-man and band leader. Just watch and listen. Nobody ever did it better, or did it cooler, than Muddy Waters.

Can’t Be Satisfied

If you like Muddy Waters - and come on, how could you not? - then Robert Gordon is a name you either already are, or that you should be, familiar with. In 2003, he produced the excellent PBS American Masters documentary about McKinley Morganfield, Can’t Be Satisfied, which is a must-watch for any music fan and which is available in its entirety on YouTube. Seriously, this documentary is worth fifty minutes of your time.

And in the same year, Gordon also released a book under the same title, which is one of the greatest music books I’ve ever read, alongside Peter Guralnick’s Elvis biographies, David Dunn’s Guitar King: Michael Bloomfield's Life in the Blues and a handful of others.

I’ve also recently written a profile on Muddy Waters for Far Out Magazine with specific focus on his album Fathers and Sons, a 1969 collaboration with Otis Spann, Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield. Hopefully it’ll be out and available to read soon.

If you enjoy my writing, you can support my work through the button below, or by sharing the articles wherever articles can be shared! Thanks for reading.

Muddy is a particular favorite of mine- I mean, that voice....

While he had recorded many records, including a few hit singles, for Chess in the late '40s and 1950s, those had largely only reached a Black audience. The Newport album (which earned him a Grammy nomination for "Got My Mojo Workin'" (deservedly so)" was really, as it was for his colleague John Lee Hooker, a debutante ball of sorts for white music fans. It was one of the opening shots of the blues renaissance of the 1960s by which Muddy and his contemporaries were elevated from juke joint musicians to folk heroes.

Thanks for a very informative piece, Matthew. Chicago Blues, especially Chess - a magnificent legacy. Muddy, Mr Wolf, Jimmy Reed, SBW… - great, original musicians. Their key recordings still sound so fresh, 70 years later.