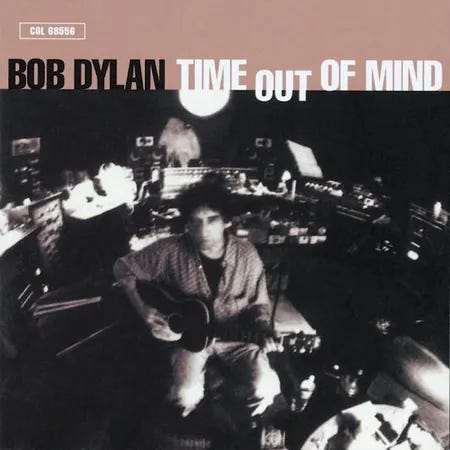

1997: Time Out Of Mind - Bob Dylan

Looking back at 30 years of music | Bob Dylan, Shania Twain, David Bowie, Nick Cave,

Go tell my companion and children most dear

To weep not for me now I'm gone

The same hand that led me through seas most severe

Has kindly assisted me home

The Lone Pilgrim

These are the lines that close Bob Dylan’s 1993 album World Gone Wrong. The lyrics were written in 1838 by a minister from Maine named Jonathan Ellis and were set to music twelve years later by ‘singing master’ Benjamin Franklin White.

It was another 143 years before they found their way onto Dylan’s album, where they close the door on the first half of his career and in doing so, pave the way for his 1997 ‘comeback’ album, Time Out Of Mind.

You can draw parallels to Dylan and his career to the words in The Lone Pilgrim: “The call of my master compelled me from home” could equally describe his leaving of Minnesota in 1960 to make a name for himself or his life on the road ever since. The very next line, “no kindred or relative nigh”, is basically the answer he gave whenever being asked about his family history early on in his career. Dylan himself is something of a lone pilgrim; wandering the world in search of song, an idea, a muse.

After a steady commercial decline through the 1980s, Dylan returned to his folk music roots with two albums of blues songs, spirituals, folk tunes and ballads in the early 1990s. When his stock was at its lowest and his critics at their harshest, he returned to the music that had given the platform on which he built his career in the first place; to the songs that had sustained him throughout it and to which he had turned to whenever his own creativity and inspiration needed reigniting. Songs like these are the source of Dylan’s power, and in his hours of deepest need they are the songs that he turns to for comfort, and inspiration. The same songs that led him through seas most severe, were about to help him bring it all back home.

After World Gone Wrong, Dylan didn’t release another album until the end of 1997. When he did, it was like he was starting again from scratch. Using the tools - the language and traditions, the forms and structures, landscape and characters that inhabit them - that he’d re-familiarised himself with on Good As I Been To You and World Gone Wrong to create a new body of songs that fit his 56 year old voice. Time Out Of Mind might sound even older than anything on the two albums that preceded it (with the exception of Froggie Went A-Courtin’, which dates all the way back to 1549). It certainly sounds older than anything else that came out in 1997.

But it also sounds fresh. It sounds new and exciting, even to listen to it today. This is the debut album by the modern Bob Dylan. This is the starting point of the Bob Dylan character that we still see on stage today. The cowboy. The gambler. The rambler. The risk-it-all trickster. King of the leering and the lurid. King of the violent, bloody, gruesome and threatening. The gunslinger and sword-wielder. The crooner. The elder statesman. The physical embodiment of American song and the defining figure of American cultural history. This is where Dylan got his act together and reasserted himself and started taking himself seriously again as a creative force, and in doing so, forced everyone else to start taking him seriously again, as well.

One way Dylan displayed that born-again self-confidence in his abilities was in the battle for control over the album between himself and super-producer Daniel Lanois during the recording sessions. The pair had worked together almost ten years previously on 1989’s Oh Mercy, and whilst tensions had arisen during the making of that release, it was nothing like what was to come during the long sessions for Time Out Of Mind.

For their 1989 album, Dylan had great songs written and ready to go but the production at times overwhelms the writing and performances. It is a strong album, but Oh Mercy is as much a Daniel Lanois record as it is a Bob Dylan release. Dylan doesn’t yet feel as comfortable or confident in his new voice and so Lanois seemed to take charge of proceedings; to shape the soundscape and craft the songs around his idea of where they should go, not Dylan's. And it’s no wonder that Dylan let him, each of his recent releases had reviewed and sold worse than the one before. He had even thought of getting out of the music business altogether. Meanwhile, Lanois (never short of self-confidence) was on top of the world and was not long coming off the back of U2’s The Joshua Tree.

While the tell-tale signs of Daniel Lanois’ production techniques are all over Time Out Of Mind - the reverb and echo and compression, the shadow sounds, muddiness and murkiness - Dylan feels more confident of who he is on this release and asserts himself more on this record than their previous collaboration. There is more depth in this music, too. It is grounded with deeper roots and a stronger foundation of blues, R&B and folk than on their first work together. Oh Mercy, in hindsight, sounds like Time Out Of Mind out of focus.

At times, the sessions for Time Out Of Mind seemed wild and chaotic. Multiple studios were tested and used across a couple different cities. Over a dozen musicians feature on the sprawling finished album. Some were recruited by Dylan, whilst others were brought in by Lanois. It often sounded like a blend of bands would end up in a room at once, not knowing who was supposed to play on what, or who to listen to or in which direction the song was going to go in. Speaking about the sessions, multi-instrumentalist Jim Dickinson would later say that “it would be like an hour to an hour and a half of chaos, and then like eight or ten minutes of just clarity and beauty. During that ten minutes we’d nail it to the wall.” (Dylan would later quip about the record that “everybody worked extra-special hard, even the musicians!”)

More than once, tensions flared up over how things should go down in the studio. Various reports have Dylan and Lanois arguing loudly, smashing instruments in frustration and even coming to blows.

In the end, the record that was released was worth all the fighting, the arguments and the confusion. It was worth the smashed guitars and dented egos. It was such a return to form for Dylan that not only was the album heralded as a roaring success - the release won 3 Grammy Awards; for Best Album, Best Contemporary Folk Album and Best Male Rock Vocal Performance - but it changed the course of his career, his public image and re-established him as an important, vital and necessary artist. Perhaps Dylan knew that he was fighting for his creative life with the making of this record. It’s no wonder that he’s not looked back since.

Side A

The musical tone for the whole album is almost set inside the first 15 seconds. We hear a scatter of notes drift across one guitar, a singular errant note from another and then a reggae-infused organ sets out the song's staccato rhythm. Dylan’s voice drifts in from some far-off land, and talk-sings “I’m walkin’, through streets that are dead”.

Here we have Dylan’s instant acknowledgement that the musical landscape he inhabits is no longer living or well-populated. He’s not about to lead us into a contemporary sounding album, but backwards in musical time through the styles of a long ago, far away past. The world where these songs come from is gone. He is part of a dying breed of troubadours, song-smiths and folk-figures keeping their memories alive, but he walks a lonely street. He is a lone pilgrim in this land.

His voice sounds like an echo. Like a shadow. Like a ghost or a spectre. It’s been compressed and distorted, but he finally sounds as old as he was trying to on his debut release, 35 years before. It suits the song perfectly. There is a lot of space in the music on this track, and yet there is something happening constantly. It is forever building, but it never overwhelms; the track breathes. It flows and comes and goes. It washes into the space all around Dylan’s voice and gives life and colour to his words.

The final line, “just don’t know what to do, I’d give anything to just be with you” inverts everything that Dylan has just sung about being sick of love. The line deftly undermines all the bravado in the song, and his true desire for reconciliation is revealed, no matter what came before. In 2005’s No Direction Home, Dylan says that “you can’t be wise and in love at the same time” and none of his lyrics sum up this sentiment more than this one.

The next track, Dirt Road Blues, was the first song recorded for the album. Whilst it does give a picture of what is to come on the record sonically, it doesn’t really stand up to the quality of either what came immediately before it or what is to follow.

A blend of Duke Robillard’s insistent guitar riff and Jim Dickinson’s playful organ parts, the song shuffles along with Dylan sounding like he’s singing from another room entirely. Everything seems far away. The basis for this track would go on to become a staple in Dylan’s latter day releases; you can find at least one standard 12-bar blues on each of his original-material releases since. It’s no wonder then, that before they started work on the record Dylan asked Daniel Lanois to listen to old rock and roll and blues records, “great early American recordings, prior to experimentation”, to understand more fully the direction he wanted to go in with this album.

Bob Dylan is as much or maybe even more of a blues artist than he is a folk singer. His first album is full of blues tunes and idioms, as is his career-defining triplicate run of Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde from the mid-Sixties. Like folk music, the blues has a communal language and lexicon, and across this album Dylan draws freely from it. Not only does he write like a true bluesman, but he can authentically sing like one now, too, with his worn and world-weary voice.

While Dirt Road Blues didn’t betray just how good some of the songs on Time Out Of Mind were going to be, you don’t need to wait long for one of the very best to begin.

Standing In The Doorway is a mystical sounding song. It is almost hymnal, and performed with great reverence for the lyric. The opening line again has Dylan walking, but this time he is walking through the summer nights with a jukebox playing low. A guitar drifts ethereally around his voice, the swell of an organ covers the ground and lightly, far off, a steel guitar cries it’s heart out. The notes hang in the air, sustained by the energy of the lyric.

When Jim Keltner announces his entrance with a hit of his snare, he pushes the understated energy of the song up a notch. Dylan’s voice is incredibly emotive, and some of the lines here are as good as he’s ever written: “don't know if I saw you if I would kiss you or kill you, it probably wouldn't matter to you anyhow”, “The ghost of our old love has not gone away, don't look like it will anytime soon / You left me standing in the doorway crying, under the midnight moon” and “last night I danced with a stranger but she just reminded me that you were the one” are all pure, essential Dylan.

Standing in the Doorway was Dylan’s most mature song up to the time of it’s release, and maybe still is, to this day. It sounds like the evolution of the thin wild mercury sound that is so emblematic of Blonde on Blonde. While Bob Dylan has a habit of shifting and evolving and reinventing himself, all of his previous versions continue to live on and work inside of him, and here we hear the evolution of his mid-60’s sound. It seems this was no accident, either, as Daniel Lanois said to Dylan at the recording session, “listen, I love "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands. Can we steal that feel for this song?”

Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands is of course the final song on Blonde on Blonde but here, Standing in the Doorway doesn’t even see out Side A of the record. There is still one more song to come before you flip the disc.

Million Miles is a loping, sneaking number. Another 12-bar blues, this time with more of a jump feel. Again Dylan feels like he is far away - maybe more appropriately so this time (“I tried to get closer, but I’m still a million miles from you”). It’s filled with great images, genuinely funny one-liners (“the last thing you said before you hit the street, gonna find me a janitor to sweep me off my feet”) and some pretty cool instrumental breaks but it still feels a little under-done. It feels like a warm up piece more than a finished track. Perhaps coming so hot on the heels of Love Sick and Standing in the Doorway it has too much to live up to.

Perhaps songs like Dirt Road Blues and Million Miles made the final cut over something like Red River Shore - my favourite song from the Time Out Of Mind sessions - or Mississippi because acoustically they fit the feel of the album more. Perhaps Red River Shore or Mississippi rejected the Lanois production treatment, or Dylan felt that the album didn’t need another long, sprawling song about religion, fading love and the shadows of the past. Songs like Dirt Road Blues or Million Miles balance out the sheer beauty and power of tracks like Standing in the Doorway, rather than competing for the same room on the record.

As we reach the end of Side A, it’s clear that Time Out of Mind is an album out of time. It sounds 100 years old. Dylan sounds 100 years old. Like he is from a different time and world altogether. Nothing else from this year sounds like this release. Nothing else from this decade sounds like this release. When accepting the Grammy for Album of the Year for this album, Dylan thanked Daniel Lanois and Mark Howard for their work on it, adding “we got a particular type of sound on this record which you don’t get every day”. He wasn’t lying. The stuff they got will bust your brains right out.

It is almost like a full band imagining of World Gone Wrong, with all new lyrics. Here Dylan is conjuring up the souls of all the ancient songs he knows from their crumbling tombs. It’s Dylan’s ‘modern’ update on the arcane, the traditional. His own folk songs, and as a result, it is Dylan’s oldest album. He sounds older on it than he did on its follow-up, 2001’s “Love and Theft”, and somehow even sounds older on it than he does on his most recent release, 2021’s Shadow Kingdom. The album feels older than time itself.

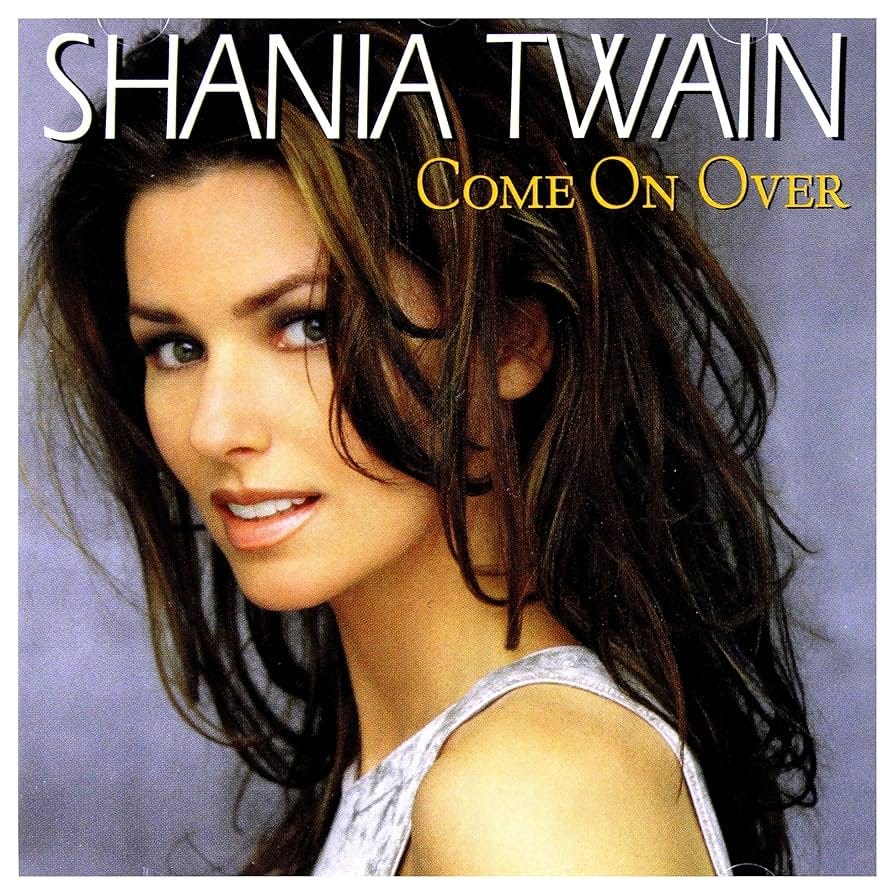

It certainly doesn’t sound like 1997. 1897, maybe. But what did that year sound like? What else came out that year? Well, there was Aqua and the Spice Girls and Wyclef Jean and The Prodigy. There were Oasis and The Foo Fighters and Sleater-Kinney. And while Dylan was singing from an old country, what did new country sound like at the time? Come on over, Shania Twain.

This album is practically a greatest hits release. You’re Still the One. When. From This Moment On. I’m Holdin’ On To Love (To Save My Life). Whatever You Do! Don’t! Man! I Feel Like a Woman. Don’t Be Stupid (You Know You Love Me). That Don’t Impress Me Much.

It’s unbelievable now, but this album spawned 12 separate singles. Most albums aren’t even twelve songs long! Well, thanks to streaming and the need to hedge your bets on what will accumulate the highest numbers, maybe they are these days…

This album is so much fun. It’s a crazy melting pot of guitars and fiddles, accordions, catchy melodies and very dated drum machines and beats. It’s as much a pop album as it is a country release.

I turned 4 just after this album came out and can vividly remember playing it on loop with my Nan on the CD player in her kitchen; endlessly singing and dancing along with her to Man! I Feel Like a Woman and That Don’t Impress Me Much (also on regular rotation in that kitchen was Whitney Houston’s It’s Not Right But It’s Okay and Maria by Blondie). It’s no wonder that a release which could appeal to both our tastes would go on to sell over 40 million copies (the eighth highest amount that any album has ever sold). Now that is impressive.

Side B

This might just about be the strongest run of tracks anywhere on the album.

Tryin’ to Get To Heaven opens up the disc with an authoritative piano run which is immediately backed up by Jim Keltner’s steady and sure drum beat. The music doesn’t let up for a minute on this one. Like on so much of this record, the organ adds depth and colour here, as does the slide guitar supplied by Cindy Cashdollar.

Dylan’s voice is as emotive here as it is anywhere in his career. At times he stretches his voice to its limit. His voice cracks and splinters, but it just helps him to wring gut-punching levels of emotion out of phenomenal lines such as “every day your memory grows dimmer, it don’t haunt me like it did before”, “you broke a heart that loved you, now you can seal up the book and not write anymore” and “when you think that you’ve lost everything, you find out you can always lose a little more”.

When you think your heart has taken as much as it can bear with the music, lyrics and vocal performance, Dylan’s harmonica washes over you like a tidal wave. He forces his band onwards. The swells of these notes are overwhelming as they coalesce with the organ, the bass, the slide guitar and crash down into the conclusion of the song.

Just like Million Miles followed Standing in the Doorway earlier in the album, Dylan again follows an emotional epic with a standard-format blues. ‘Til I Fell In Love With You is the strongest of the 12-bar tracks on the album, though.

An organ stab announces the song and snaps your attention and focus away from the remnants of Tryin’ to Get to Heaven. Bob Britt - who would later join Dylan’s touring band in 2019 - plays a pulsing, rippling guitar part here but the real star of the show is Jim Dickinson’s electric piano. Underneath Dylan’s vocal, there is a real funky heart and undercurrent to this song. As it moves along, it begins to swing more and more thanks to that keyboard part blending with the bubbling, building drum beat. As with everything else on this record, there are great lyrics throughout and they are delivered with Dylan’s most dynamic vocal on the album.

Next, Not Dark Yet rolls in on a crest of shimmering guitars. Once Dylan starts singing, it very quickly becomes clear that this is a beautifully crafted song. It has as much or more in common with Tin Pan Alley and the Great American Songbook than folk music or the blues. This is Dylan at his craftsman-best.

He has always had an uncanny knack of coming up with profound turns of phrase that feel intimately familiar, even the very first time you hear them. Like they are part of the common tongue. “Behind every beautiful thing there's been some kind of pain” feels like an ancient proverb. He also has a knack for blending that profundity with a more routine lyric, or a seemingly forced rhyme ("she wrote me a letter and she wrote it so kind, she put down in writing what was in her mind”) and still selling the lyric with his delivery so that it sounds just as important.

This, perhaps more than any other song on the album, gives us an insight into where Bob Dylan really felt that he was at in the lead up to the release. His star had long since faded, his records didn’t sell well and they reviewed even worse. He was often spoken of in terms of his past glories and achievements (“sometimes my burden is more than I can bear”) and not in terms of what he had left to offer. He wasn’t getting any younger and it may have felt like it was time to do-or-die with his next release. His back was to the wall, as it so often has been in his life, so it is not surprising that at this point in his career the line “it’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there” would flow from his pen.

But in that word ‘yet’ is the hope that he could keep the darkness at bay. In that word ‘yet’ is the acknowledgement that while the finishing end may soon be at hand, it wasn’t quite knocking on the door. He was going down slow, just barely staying alive but he at least he was still alive and kicking.

In Not Dark Yet Dylan intones that “I don’t even remember what it was I came here to get away from”. In the 60s and 70s he had to constantly be on the move to get away from intrusive and invasive fans. Fans who were known to regularly comb through his rubbish bags, climb his roof and break into his house looking for answers to the meaning of life and, more importantly, the meanings of all his songs.

As David Bowie put it on his 1971 track, Song for Bob Dylan:

Some words had truthful vengeance

That could pin us to the floor

Brought a few more people on

And put the fear in a whole lot more

His appreciation for Dylan didn’t diminish through the years and in early 1998 he would record a cover of Tryin’ to Get to Heaven, but before he got around to that, he had an album of his own out, 1997’s Earthling.

Bowie, like Dylan, was always restlessly shifting and trying new things as an artist but the turn he took in the late 90s was perhaps more bizarre than any other in his career. Whilst at 56 Dylan was embracing the past with his sound, Bowie (who had just turned 50 himself) had both eyes set firmly on the future with his latest musical move. Looking back now his full-bodied embrace of the dance, electronic and drum and bass scene feels like that at this point he’d become more of a trend-follower than trend-setter, though.

Space Oddity. Life on Mars. Starman. Loving the Alien. Hallo Spaceboy. It’s no little wonder that David Bowie even knew what an Earthling was.

Side C

Talking to Uncut magazine in 2008, drummer David Kemper said:

“I heard this disco record with a Cuban beat, and when I got to the studio, I sat back at the drums and I slowed the beat down, and turned it upside down, and I was just playing, and there was nobody there. No one was expected for a half hour. So I was playing this drum beat, and then Bob snuck up behind me and said, ‘What are you playing?’ I said, ‘Hey Bob, how are you today?’ He said, ‘No, don’t stop, keep playing, what are you playing?’ I said, ‘It’s a beat. I’m just writing it right now’. ‘Don’t stop it. Keep doing it’. And he went and got a yellow pad of paper and sat next to the drums, and he just started writing. And he wrote for maybe ten minutes, and then he said, ‘Will you remember that?’ And I said, ‘yeah, I got it’. And then he said, ‘all right, everybody come on in, I want to put this down’.

Well I got it in my head, and by then everyone had arrived and tuned up. And take one, he stepped up to the microphone, and [sang] ‘I’m beginning to hear voices, and there’s no one around’. And I think we did two takes, and then he said, ‘All right, let’s move on to something else’. I remember Daniel Lanois wasn’t happy; he didn’t like it. It was one of his guitar breaking incidents. He said to Tony [Garnier] and I, ‘the world doesn’t want another two-note melody from Bob’. And he smashed a guitar. So I thought, well, there goes my chance of being on this record.

But David Kemper did make it onto the record. Cold Irons Bound blasts open Side C of the album and it is a force to be reckoned with. A staggering feat of creativity and sudden inspiration, this is a power surge of a song. For something that was written on the spot in ten minutes, the lyrics are unbelievably locked in. “Well the walls of pride high and wide, can't see over to the other side / It's such a sad thing to see beauty decay, it's sadder still to feel your heart torn away”. “There’s too many people, too many to recall / I thought some of them were friends of mine, I was wrong about them all”. “Well the winds in Chicago have turned me to shreds / reality has always had too many heads”.

Most artists would agonise over lines like these, refine them over time, but Dylan can conjure them up on the spot. He may be bound in cold iron chains in the song, but with his creativity and imagination, Dylan gives himself an incredible freedom to move.

Buried deep down in this album, Make You Feel My Love might be able to stake a claim as being Dylan’s most well-known song. But not in this version. Adele would make this song an unavoidable international hit in 2008. The success she had with the song was so all-encompassing and all-conquering that it wiped Dylan’s part in it out of public consciousness. It might be the reason that so many Dylan fans dismiss it and deride it, but to do so is to overlook a great, well-crafted and evocative song.

Supported by his own piano, Tony Garnier’s bass and Augie Meyers on organ, Dylan aches his way through the lyrics. This is another Tin Pan Alley infused composition and so it’s fitting that it has become a modern standard.

Musically the song is incredibly similar to Simple Twist of Fate, from his 1975 masterpiece Blood on the Tracks. Taken side by side, the two can be seen as a pair. Where in the earlier song the narrator is left alone, searching and waiting for his love to return to him, in Make You Feel My Love he is not letting her go without a fight. He learnt from his heartache how it feels to be left by his lover and is unwilling to go through the pain of it all twice, and so the passive “maybe she'll pick him out again, how long must he wait? One more time for a simple twist of fate” from the old song becomes the active “I'd go hungry, I'd go black and blue / I'd go crawling down the avenue / No, there's nothing that I wouldn't do, to make you feel my love” promise in the new one.

As this song fades out, the next one fades in with a drag on the guitar and a subtle funk-infused rhythm section. The music feels like it’s being played through a wall, muffled and warped and coming to you from another room. Once again, the organ is the most important instrument in shading the sound, filling the spaces between what everyone is playing and what Dylan is singing.

Musically, this might be the most interesting side of the whole album. Cold Irons Bound blends Kemper’s Cuban rhythm with menacing southern guitars and is full of diminished chords. Dylan’s idiosyncratic piano is all over Make You Feel My Love, and while it may sound like a relatively standard major-to-minor chord progression, it also also includes some interesting augmented chords in the bridges. Can’t Wait is a melting pot of funk, blues, rhythm and rock.

This one doesn’t sound a million miles away from Million Miles but it is more focused, more locked in and direct. Dylan sounds more confident in his delivery, but once again is straining in his vocal performance. This time, he is not straining for emotion but for menace. He sounds grizzled. He sounds pissed-off. He is not saying that he’s so excited that he can’t wait, but that he has finally run out of patience. He’s at the end of the line, the end of the world. The end of time and out of his mind.

It’s mighty funny, the end of time has just begun

Oh, honey, even after all these years you’re still the one

While I’m strolling through the lonely graveyard of my mind

I left my life with you somewhere back there along the line

I thought somehow that I would be spared this fate

But I don’t know how much longer I can wait

The only other balladeer sailing in similar waters that year was Nick Cave. But The Boatman’s Call sounds more like a record that belongs in this time period, in this world, even. Both releases explore similar lyrical themes and elements of love, loss, faith and mortality and Nick Cave is very much rooted in tradition like Dylan is. But his work feels more like it was tuned and crafted with a human hand, whereas Dylan’s can feel more like he has been struck by divine intervention. Time Out of Mind feels more like it came up out of the big muddy river than The Boatman’s Call does. More-so than Cave’s release, it is of the land and the soil and the trees and the air and water and wind.

Both The Boatman’s Call and Time Out Of Mind explore mystical elements of religious faith, as well as the faith that is born from love (and the ways in which love can test that faith). Talking to David Gates from Newsweek around the time of this album’s release, Dylan said “I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don't find it anywhere else. […] That's my religion”. Similarly, Nick Cave sings in Into My Arms that “I don’t believe in an interventionist God” and of Angels and Christ, before admitting “but I believe in love”. Dylan shows time and time again on Time Out Of Mind that he does, too.

Side D

Highlands. At the end of this long, meandering and winding album comes an epic. A wandering, drifting ramble through the Scottish highlands of Dylan’s mind. This hypnotic, waking fever dream of a song feels like Dylan’s touring schedule: never ending. It has everything you want from a Dylan lyric: humour, history, reality, unreality, cultural references, storytelling telling the absurd and the mundane. Every song that Dylan had written before is here in this one if you listen closely enough.

When finally the long song ends and with it, the long album, it feels like it was never even playing in the first place. The silence feels like thunder, and any minute you’re expecting to wake up from a dream. You’re not sure if you were riding in a buggy with Miss Mary Jane, or if she even ever had a house down in Baltimore. You’d be sure that you imagined the whole album, if only for the fact that you can still hear it, over the hills and far away. Drifting in on a jukebox playing low. In your head, at least, it is still playing. It circles around your skull. On, and on. Neil Young and Erica Jong. Somewhere, in another world, it is playing and it never stops.

And that’s good enough for now.

Elsewhere in 1997…

Highest selling single (UK): Something About the Way You Look Tonight / Candle in the Wind 1997 - Elton John

Notable releases:

Blur - Blur

Daft Punk - Homework

Green Day - Nimrod

Mariah Carey - Butterfly

Missy Elliot - Supa Dupa Fly

The Notorious B.I.G - Life After Death

Paul McCartney - Flaming Pie

Radiohead - OK Computer

Spice Girls - Spiceworld

The Verve - Urban Hymns

This is not the first time I’ve written about Bob Dylan. In fact, I’ve written a whole book about him! If you liked this article, you can buy a discounted copy at the link below with the code ROUGHANDROWDYWAYS or grab an eBook for only 99p!

Thanks for this piece, Matthew, I really enjoyed it. The songs on TOOM are wonderful material to work with and, as Graley says, you do justice to it.

Bravo! TOOM is a bit of an obsession with me, and you do justice to its dark majesty in this deep meditation, Matthew. I like the lead-in with "Lone Pilgrim," as if the TOOM walker hasn't just been traveling for miles but for centuries, millennia, since our first amphibious ancestor crawled out of the primordial ooze, or Cain drew first blood and got his walking papers to the Land of Nod. Thanks for getting my mystical weather vane spinning with this excellent post, Matthew!