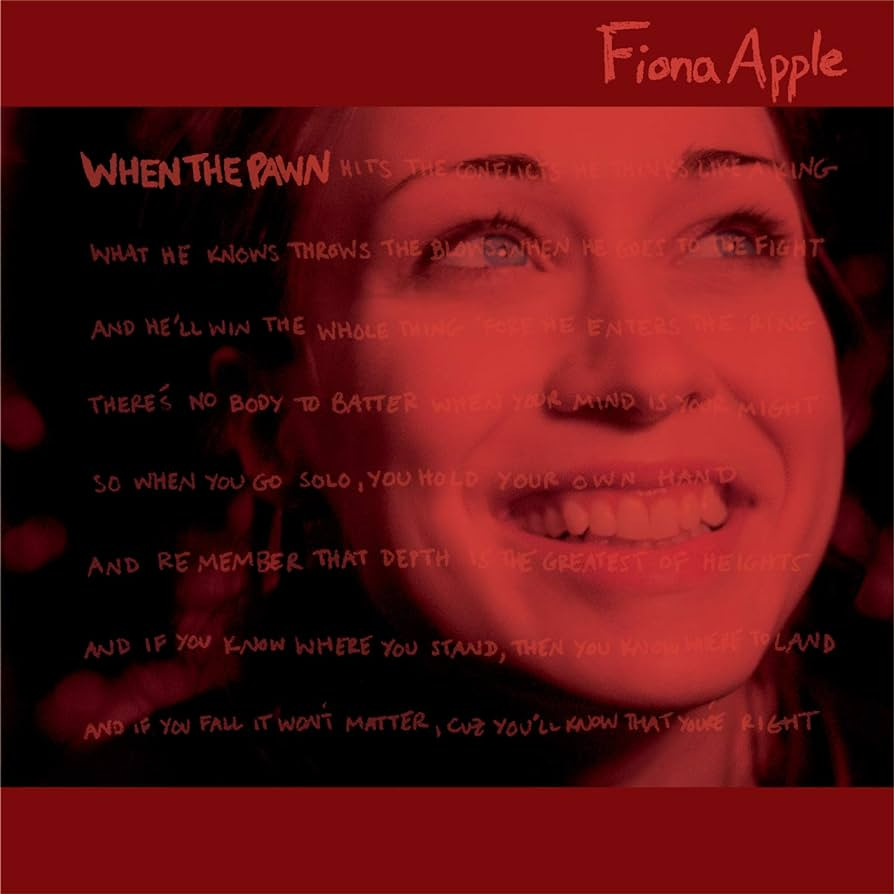

1999: When the Pawn... - Fiona Apple

Looking back at 30 years of music | Fiona Apple, Wilco, Will Oldham, Tom Waits

Sometimes you hear a new artist and they grab you instantly. So much so that you feel a compulsion to drop all interest in any other music altogether and obsessively explore their entire back catalogue, playing them on repeat until you have seared their songs into your brain. Some artists creep up on you over time; their music merely amenable to you at first but then one day revealing to you a pathway to a much deeper connection.

Sometimes you know something you hear is good, even great, but that you aren’t quite ready to fully embrace, feel or get it yet. I had this with Leonard Cohen and Tom Waits. When I first heard them, I knew that I needed to go away and do more work before I could come back and fully understand and appreciate them. I still haven’t quite caught up to Joni Mitchell yet, but know she is great and that one day I will fall in love with her music.

A combination of all these things happened to me with Fiona Apple. I’d heard her name spoken in reverent tones by people whose opinions I respected and trusted. I knew that other songwriters that I love in turn loved her. I adored her cover of Across the Universe even more than I like the original by The Beatles, and think that she set the standard for the Cy Coleman tracks Why Try to Change Me Now and I Walk a Little Faster. Her rendition of River Stay Away From My Door moves me in a deeply affecting, spiritual way right down to my core; to listen to it feels like having an almost religious experience. Bob Dylan even recruited her to play piano on one of his greatest, and most important songs.

And yet, I just couldn’t get my head around any of her original compositions that I’d heard.

I tried again and again with Fetch the Bolt Cutters when it came out, to such critical acclaim, but couldn’t find a way in; no point of entrance from which to understand what I was hearing or feeling. In fact, I think what I was feeling was almost a visceral rejection of the album. My mind and ears would shut down any attempt that I made to come to terms with or enjoy it. It felt far too over my head to comprehend. I tried listening to the album that preceded it, The Idler Wheel, and it left me feeling the same way, so I assumed the rest of her work would do, too. I assumed that like these two albums, all of her work would be too advanced for my understanding, too complex for me to comprehend.

But I was wrong about that.

Last year I decided to try again, this time listening to 1999’s When the Pawn…. From the very first hammered note on the piano on the opening song, On the Bound, I was transfixed. I was turned around and I was hooked. I stopped everything else that I was doing and just listened. When the album finished almost 45 minutes later, I took a breath and went back to On the Bound and listened to the whole thing again, and then again.

When the pawn hits the conflicts he thinks like a king

What he knows throws the blows when he goes to the fight

And he'll win the whole thing 'fore he enters the ring

There's no body to batter when your mind is your might

So when you go solo, you hold your own hand

And remember that depth is the greatest of heights

And if you know where you stand, then you know where to land

And if you fall it won't matter, cuz you'll know that you're right.

Much of Fiona Apple’s debut Tidal is centred around her voice and her piano, and at first listen it can seem that When the Pawn… is simply picking up where she’d left off three years prior.

But the syncopated piano playing that brings us into the new album feels different than the softer, warmer playing we heard on the majority of the first record. Immediately here it is menacing, stalking, forceful and on the move. In the twenty or so seconds that Fiona Apple is playing the piano before she starts singing, you can already sense her self confidence. The chords are pounded and then dragged into the next one. Her playing is on the bound and backed up by Matt Chamberlain’s minimal yet authoritative and pounding drumming.

When Fiona Apple’s voice comes in, she too sounds different than on her first album. Still only 22, she sounds like she is singing with all time in her voice. Like she has lived a thousand lives in the last three years and the experiences from all of them are leaking into her voice here. When she sings on this album, it sounds like she is using the voices of all the women that have inspired her, and all the women that she in turn will inspire.

She sings the opening verse somewhere between a whisper and a bellow. It is quiet, but it cuts right through. She lays out everything that we need to know about what we’re going to hear over the course of the album succinctly in the first words that we hear.

All my life is on me now

Hail the pages turning

And the future's on the bound

Hell don't know my fury

It doesn’t even take a minute to get to the first chorus on the album - she is wasting no time here - and Apple ramps right up from her quietly forceful voice into a full on roar for it, repeating the “you’re all I need” refrain before everything drops out and she drily intones, “and maybe some faith would do me good”.

In the next verse, Apple crams in so many words that she almost starts rapping, but then in the bridge the lyrics drop away and become sparser, emphasising the urgency of one set of lyrics and the demand in the other. Her voice switches from breathless to breathy in the blink of an eye, and in the bridge we hear the full force of Fiona Apple’s voice for the first time on the album. She opens up her lungs to really get around the lines and you can hear her voice echoing in from somewhere outside the studio, somewhere outside herself, even. You can hear every person who has ever made a similar plea being channelled through her as she sings

Baby, lay your head on my lap one more time

Tell me you belong to me

Baby, say that it's all gonna be alright

I believe that it isn't

And now we hear Patrick Warren’s Chamberlin take centre stage. The organ sound is carnival-esque, but tinged with darkness and shadow. It feels like we’ve entered into a circus at the end of the world, or else in the underworld. All hell has been let loose. Apple belts out one more chorus and then all the instruments evaporate away before crashing right back in again. Producer Jon Brion’s guitar stabs and hacks its way into the mix, duelling with the organ, piano and bass for space.

Nearly five and a half minutes have gone since the album began, and it’s already clear that Fiona Apple has grown in stature since her debut. Barely has the first song finished, when the urgent piano of To Your Love races into our ears, once again undercut with that warm bass sound and insistent drumming. Sonically and structurally, this song is pretty similar to On the Bound, but where the first track is staggering and striding, To Your Love is manic and frantic and hurries along with urgency. The chorus cascades and tumbles underneath her menacing vocal.

Listening to this album for the first times 25 years after it came out, it retains a novelty and a newness, an inventiveness, that I haven’t heard from many (or really any) other albums that have been released since.

Fiona Apple feels fresh, unique and entirely herself throughout the record. There is never a moment on this album where she feels like anyone but Fiona Apple, or where it feels that she’s trying to be anyone but Fiona Apple. Writing about her in 1997, Spin Magazine said that “Fiona Apple is a rock star, and before she has fully become a person, she has become a persona. It's taking her some time to decide which part of her is the image, and which part is real.” There is nothing but the real deal on When the Pawn…

Everything on this album feels like she is inventing the form that she’s working within in real time; that she is conjuring all music and not just her own, and yet her songs are so well structured and fashioned, so precise, that she has obviously done the work of mastering her craft, refining her writing and growing into her playing and singing. From listening to this record, it is obvious that Apple has done the work of living inside plenty of other people’s songs in order to learn how to write her own, and really understand how the form and structure of a song should come together.

It might help that she comes from such a rich lineage of performers and creatives. Her mother is a singer, her father an actor (the two met on the set of the 1970 Broadway musical Applause, starring Lauren Bacall, which they both featured in). Her creative roots grow down even deeper, too; her maternal grandmother was the vaudeville performer, dancer and singer Millicent Green whilst her grandfather Jonny McAfee was a saxophonist, clarinettist and flautist for orchestras such as Tony Pastor’s and Benny Goodman’s, and he also sang with the Harry James Orchestra.

Considering this stage and show heritage, it is no wonder that Fiona Apple embodies and sings the Great American songbook as well as she does, and that she clearly has a deeply rooted connection with the repertoire. She has lived inside those earlier songs, worn them in and worn them out, but yet her own music is very far from standard.

She has also spoken about how deeply affected and changed she has become when listening to albums such as Bob Dylan’s Desire or Kate Bush’s The Kick Inside, or works by Patti Smith, and also how much the hip-hop that she grew up surrounded by became an element in her own writing.

On this album, she starts to draw together all of these influences; pairing the simplicity of the lyrics of the Great American Songbook and vocal inflections of its great female practitioners with more surreal lines, turns of phrase or stream of consciousness outbursts and a sneer of confidence and indifference that wouldn’t be out of place on a mid-60s Dylan record. She is equal parts reverent, profound and precocious throughout.

The hip-hop influence can be heard coming in through the drum patterns and rhythms across When the Pawn… but it never dominates or tips over into pastiche. The influence and essence are present throughout without ever becoming appropriation (a trap that a lot of more contemporary singer/songwriters have fallen into), and this helps keep the production from becoming too grounded in any one time, or linked too heavily to any particular influence or trend.

Writing outside of time is the best way to keep your art timeless, and to keep it from being rooted too deeply in the culture that it was created in. By mixing up her influences from myriad corners of the past and combining them with her own unique voice and creativity, Fiona Apple managed to create a record that will endure through the ages; it sits outside of any one time and can be enjoyed in all of them.

It is interesting that given the amount of influences that come through on the album that it manages to sound so unique.

When Fiona Apple is working on new music, she stops listening to anything else by anyone else and perhaps this is one of the reasons that she creates songs and sounds that are so unique, so singular and so her own.

A lot of contemporary writers are so rooted and grounded in themselves and their own personal stories and as a result they can become disconnected from the wider world. But Apple has got such an anchor in her influences, whether they are musical, cultural or literary, that when she goes away from them to explore herself and her stories, she is always grounded in something bigger than and outside herself. Where others use their personal stories to connect the wider world to themselves, Fiona Apple uses her own personal stories to connect with and to the wider world.

Her innate ability with words and her deep and rich understanding of how to craft a song is what sets her apart from other writers working in this space today, and what will help her music endure where others’ may not.

She writes with an urgency, everything feels like it is overflowing from her for the first time every time that you hear it, and yet it all feels so incredibly refined, crafted and perfected. She has a pop songwriter’s sensibility and could probably write chart-topping hits if she turned her mind to it, but she uses everything she has learned and felt to craft something more interesting, more challenging and most likely, more lasting, instead.

Love Ridden is one of the clearest examples on the album of how her voice and writing have matured since her first record. The song might not sound out of place on Tidal, except for the fact that Apple sounds more self-assured and in control now. Her mellifluous voice glides from her lower to upper registers at times with such ease, and her piano carries the song behind her. The lyrics are tender, full of longing but also the wisdom to know when love is no longer enough

I want your warmth, but it will only make me colder when it's over

So I can't tonight, baby

No, not baby anymore

If I need you, I'll just use your simple name

Only kisses on the cheek from now on

And in a little while, we'll only have to wave

Speaking to Richard Harrington of The Washington Post in 1999, Apple said that, “if you are a new artist, you are fair game for everybody and you're not going to gain any power until the second time around”. On this album, her powers are on full display for all to see, and no track shows her powers off more than the next one, the centrepiece of the record and one of the most brilliant songs ever written, Paper Bag.

In her album review for The Boston Globe, Joan Anderman said that Paper Bag “owes equally to Kurt Weill and Paul McCartney”, and it is true that the song has a distinctly European flavour as it builds, but it could equally have been likened to something by Randy Newman with it’s rolling piano part and score-like strings and brass. Never mind who else it sounds like, it is pure Fiona Apple.

One of her greatest strengths as a writer and singer is making her personal experiences feel universal. These songs aren’t just about what it feels like to be Fiona Apple, they are about what it feels like to be a woman. With them, she can speak to and speak through her audience. In her words, you can hear her channelling not just her own experiences, but those of so many other people. Lines such as “I know I'm a mess he don't want to clean up”, “I went crazy again today looking for a strand to climb” and “hunger hurts but starving works when it costs too much to love” so magnificently express her inner turmoil, frustrations and longings and it is no wonder that they have connected and resonated with so many people, for so long.

I delight every time at the simple genius near the end of the second verse, when she sings the so casually cool, cruel and dismissive

He said "it's all in your head"

And I said “so's everything”, but he didn't get it

I thought he was a man but he was just a little boy

As the song builds towards its finale, Apple’s voice grows in power and emphasis as she repeats the chorus again and again. The song steadily builds in stature, in power and confidence without ever being forceful or overbearing, without ever becoming overwhelming. We can hear her fill her lungs to get her through each repetition of the chorus as she pushes on to further heights and provide the unshakeable power to press on. Her voice wavers, but never falters. We can truly feel and hear how much she means what she sings in every single syllable.

The string and brass ensemble build their way into the piece, which begins to feel like a marching band; it could be the sound of an army of women empowered by Apple’s words marching on the men who have mistreated or abandoned them. Before it can burst, the rhythm of the song floats away as if on a breeze, as if it had all been a dream.

And from a dream to a nightmare, with the next track we’re back in the menacing carnival underworld of On the Bound. Jon Brion’s viper-like guitar sets the tone over the funk infused drums, hazy synths and piano, stabbing its way through the intro to A Mistake. On the whole, this is a piano-focused album, the songs are based around Apple’s playing and singing, but here it is the guitar that drives the song along.

Throughout the track, Apple sings that she has acquired a taste for a well made mistake, but none of the musicians are making any here. The drumming across the whole record is excellent - it propels everything - and on this song it is as good as it gets anywhere. On top of that drumming, Apple’s pounded piano part and Mike Elizondo’s bassline, Brion’s guitars sweep and stoop, swirl and stab and smother and sear as they layer up to create a chaotic flurry of activity.

Just as on Tidal you could hear the seeds of When the Pawn…, so too on this album can you get glimpses at the Fiona Apple songs to come. Limp could fit on The Idler Wheel, Fast as You Can would not sound out of place on Fetch the Bolt Cutters and Get Gone would be right at home on Extraordinary Machine.

The last of these contains some of Apple’s most authoritative singing and playing yet. She is at her full power here as she belts almost every word with verve and vigour, with her final victory in sight. With this song she is taking full control, taking full responsibility and putting herself first because the man she’s singing to sure isn’t about to do any of that for her.

Cause I've done what I could for you

And I do know what's good for me

And I'm not benefiting

Instead I'm sitting

Singing again, singing again

Over the course of the album, she has been at times both resistant and receptive to love; she’s been ridden by it and gotten rid of it. Her anger has come and gone and come back again. She’s been left and let down and now it’s her turn to do the leaving, on her terms and in her own time. It's time the truth goes out.

But then, once the surety and confidence and swagger of Get Gone subsides, comes the resignation of I Know. The provocative opening phrase “so be it, I’m your crowbar, if that’s what I am so far” was inspired by a former lover who told Apple that she was his crowbar, in that she’d pried open a new life for him but now he was leaving.

In Get Gone she was angry that “he won't admit to it”, but here now, after the fact and deep in thought, she lets on that she doesn’t need any admissions of guilt anyway. She already knows everything that she needs to, and she probably always did from the start.

And I will pretend

That I don’t know of your sins

Until you are ready to confess

But all the time, all the time

I’ll know, I’ll know

The song is a beautiful way to end this incredible album. It is an enchanting, beguiling and heartbreaking wander through the wasteland of every ruined relationship on the record. Joined by the legendary Jim Keltner on drums, Mike Elizondo on upright bass and a swelling string section, Apple’s voice glides gracefully through her full range, through every emotion she has and through all time. It leaves you pried open and ready to enter your new life, changed by having experienced such a perfect and complete album.

Writing in the New York Times in 1997, Ann Powers got to the core of Apple’s essence far better than any of the men writing about her at the time did, “Ms. Apple's seemingly innocent audaciousness exemplifies the vitality of today's young women, perhaps the first generation to begin with a sense of themselves as a force to be reckoned with”.

That sense helped give Apple the ability and the confidence to sing over the heads of her critics, knowing that her words would outlive and outlast theirs. Reviews for this release at the time were often a strange mix of positive and dismissive. Yes, she’d written and recorded a brilliant album but who cared, she was just another girl making Men’s Music.

Rob Sheffield tried to project his feelings about her onto the readers of Rolling Stone, writing in his his 3.5 star review for the publication “but if you find this twenty-two-year-old bad seed intolerably self-indulgent and were rooting for her to crash and burn with a humiliating second-album spaz-out - admit it, you were - you lose”, while Chip Chanko only briefly managed to mention the album in between writing about how ill he was at the time and how much he hated her up until recently in his 8.0/10 review for Pitchfork.

By far the worst writing of all came from the NME, with Piers Martin’s 5/10 review containing such thinly veiled misogyny, condescension and a lack of class that it’s no wonder the publication has no reference to either it’s review or the reviewer on their website now (perhaps it’s a history of this kind of writing that led the NME to going out of print in 2018, and has since led them to allegedly using AI to generate some of their web-articles).

Even if the only album that Fiona Apple had ever released was When the Pawn…, I would believe that she was one of our greatest contemporary songwriters, if not the best; that she is a true genius both lyrically and musically. But it’s not just this album that proves the point. There were flashes on Tidal, and since then she has asserted her creativity, complexity and genius on Extraordinary Machine, The Idler Wheel and, perhaps even more so than anywhere else, on Fetch the Bolt Cutters.

Elsewhere in 1999…

Wilco released their first album of original tracks since 1996’s Being There with their new record Summerteeth. It sounds exactly like the album you’d release when you’re right in between making Being There and Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. She’s a Jar, Nothing'severgonnastandinmyway(Again) and Via Chicago are some of my all-time favourite Wilco tracks and are still highlights of their live shows to this day.

Will Oldham introduced the world to Bonnie “Prince” Billy with his sixth album I See a Darkness. Johnny Cash covered the album’s title track on his 2000 release, American III: Solitary Man. Oldham would re-record and re-release the song himself in 2012, complete with a video featuring Angel Olsen and Emmett Kelly.

Tom Waits was back after six years away with his latest album, and first on the Anti- label, Mule Variations. This has become one of his most well regarded releases (some feat, the man hasn’t made a bad album yet) and it’s no wonder with songs like Lowside of the Road, Hold On, Get Behind the Mule; the gorgeous House Where Nobody Lives, Picture in a Frame and Come On Up To The House and the equally sinister and hilarious What’s He Building?. Possibly even more than any of his other albums, it’s a true mix of brawlers, bawlers and bastards.

Tom Waits and Fiona Apple are both rumoured to be working on new music right now. In my head they travel over similar terrain musically; they’re both very experimental, not afraid to take chances and work on their own terms, and both of them are among the most engaging, interesting and exciting artists that we have on stage, in interviews and, especially, in the studio. I can’t wait to hear what the hell they’ve been building in there.

Notable Releases:

Last UK Number 1 of the 90s: Westlife - I Have a Dream / Seasons in the Sun

Last US Number 1 of the 90s: Santana - Smooth (feat. Rob Thomas)

Last album released in the 90s: Jay-Z - Vol. 3: Life and Times of S. Carter

Blondie - No Exit

David Bowie - Hours

Dr. Dre – 2001

Gabrielle - Rise

Lou Bega - A Little Bit of Mambo

Macy Gray - On How Life Is

Mary J. Blige - Mary

Robbie Williams - The Ego Has Landed

Ricky Martin - Ricky Martin

The White Stripes - The White Stripes

That’s it for the 1990’s, and for the 1900’s! Next week our musical journey leads us into a new millennium.

I suppose since I was there at the beginning, with Tidal, my way in was in real time, thus easier to access. Great piece here! I'm revisiting 1999 in a couple of weeks myself, and this album will definitely be on the list.

Oh boy, I had this album on high rotation back in then! Thanks - great post!