2001: "Love and Theft" - Bob Dylan

Looking back at 30 years of music | Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, The Strokes, Wilco, Gillian Welch, Mercury Rev

A lot of Bob Dylan’s albums can be grouped together in threes. The three album run of Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde is the most famous and lauded of his trilogies. There is a through-line that links Blood on the Tracks, Desire and Street Legal. Then there’s the gospel trilogy of Slow Train Coming, Saved and Shot of Love. Beginning in 1997, there is Time Out of Mind, “Love and Theft” and Modern Times. After that, came his Great American Songbook trilogy of Shadows in the Night, Fallen Angels and Triplicate (or was Triplicate a trilogy all by itself?).

Dylan knows the power of the number 3, writing in Chronicles that “I’m not a numerologist. I don’t know why the number three is more metaphysically powerful than the number two, but it is”.

According to numerology.com, the 3 is a “communicator through and through and shines in all forms of expression. It is bursting with thoughts, ideas, dreams, and musings and must let them out to the world”, and “it realizes the written and spoken word can only take us so far. Words can communicate ideas, but to express our feelings we need the unparalleled power of art”.

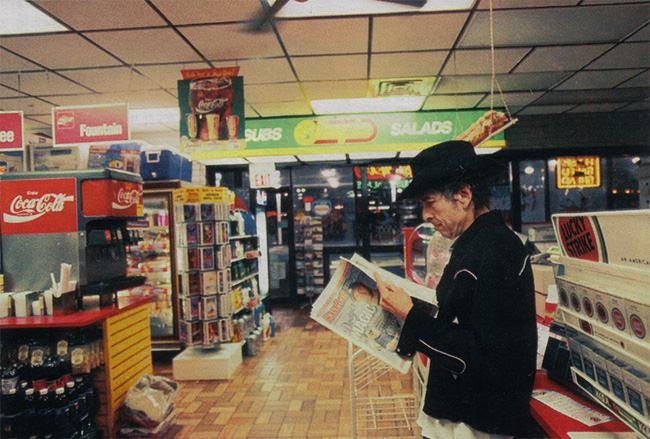

All of which could perfectly describe Bob Dylan’s 2001 album “Love and Theft”. Dylan himself is a master communicator, and this record is bursting at the seams with thoughts, ideas, dreams and musings. It feels so vital and urgent that nobody could have kept it from getting out into the world. And it doesn’t just rely on the words, this is a living and breathing musical revue. This is an album that makes you move, in your body and in your spirit.

At a press conference in Rome ahead of the album’s release, Dylan was asked “would you say this is the first record of yours that people can dance to?” (the man asking the question continues, “we’ve listened to it all morning, and-” Dylan interrupts with a grin in his voice, “and you’ve been dancin’ all mornin’?”).

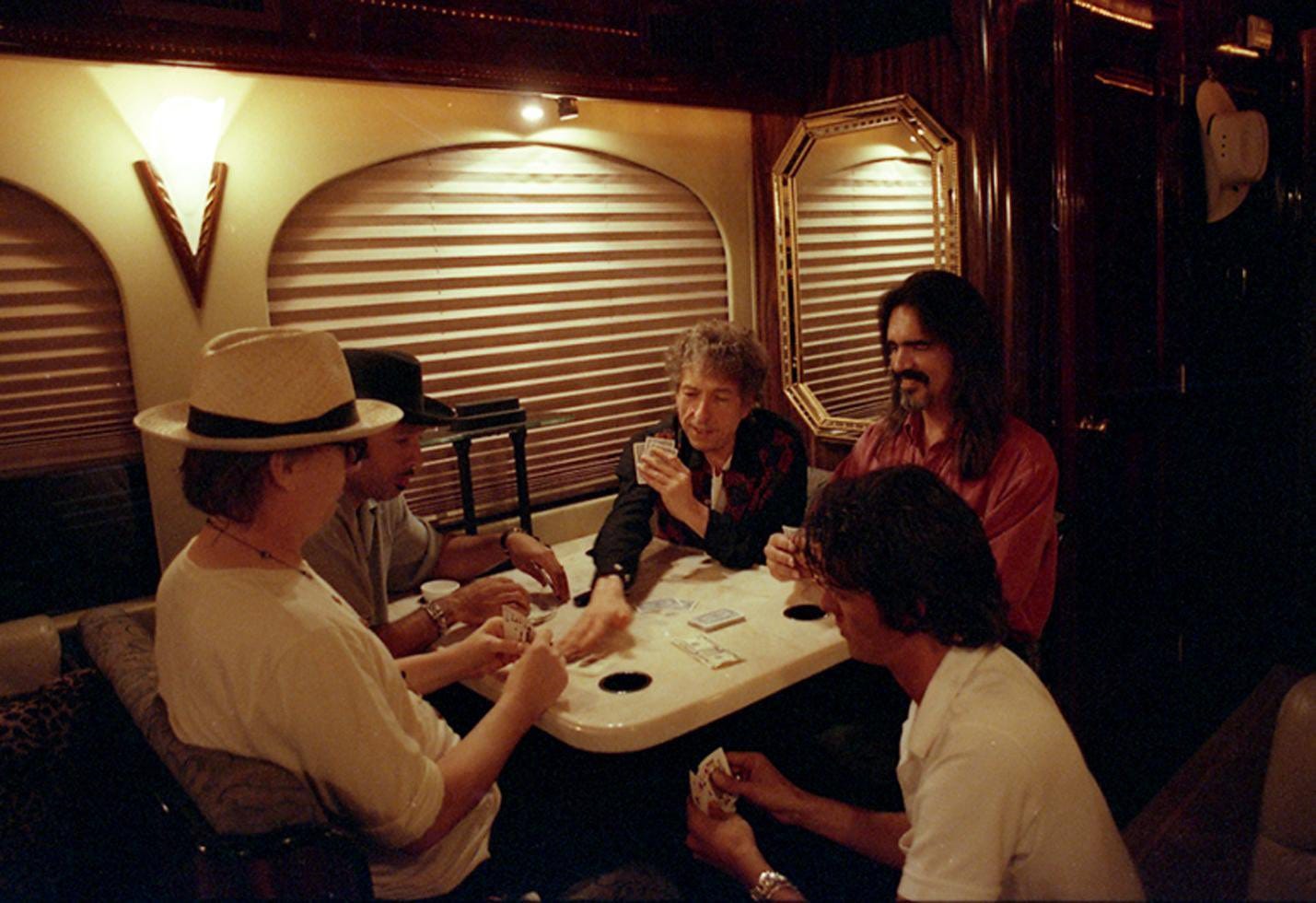

It is a very danceable record. It’s full of jump rhythms and breakneck blues’. It’s full of life, overflowing with wailing guitars and fiddles, riffs and licks. It swings and it swaggers and it struts. Michael Bloomfield would have been right at home playing on this album, if only he'd lived long enough to do so. It’s one of Dylan’s most fun records to listen to, perfect for long, late summer evenings and get-togethers.

In the Rome press conference, Dylan describes it as a “greatest hits album, without the hits” and he’s right. It’s a perfectly balanced album, every song is pulling in the same direction and there is no one track that outweighs any other. Every song has its place here, and they each come together to create a coherent whole. Perhaps that’s why there were no singles pulled from the album; why nothing from this record could break free and become an individual hit on its own.

It might just be Dylan’s most complete album, his crowning achievement as a recording artist. As on all his best albums, every Bob Dylan turns up on this record; everyone he’s been and everything that’s made him who he is.

And the album is so strong, so alive and complete not just because it is made up of great songs, but because those great songs are made up of great songs. They’re made up of great literature and great works by other great minds, too.

Speaking at the press conference in Rome, Dylan said that “most of the songs have some traditional roots to them, if not all of them”.

He’s not kidding. Every track on “Love and Theft” is deeply rooted, drawing musically from early R&B and blues songs (such as Johnny & Jack’s Uncle John’s Bongos) or pre-war Pop (Gene Austin’s The Lonesome Road and Snuggled on Your Shoulder (Cuddled in Your Arms) by Bing Crosby to name just two).

On top of the musical borrowing and adaptations, the lyrics are richly intertextual. Dylan quotes other song lyrics and draws as well from literature and film dialogue. He references Sonny Boy Williamson II’s Your Funeral and My Trial and borrows lines from Victoria Spivey’s Dope Head Blues (both just in Cry a While alone); quotes Groucho Marx’s Otis B. Driftwood character from A Night at the Opera (“Room service? Send up a larger room”, in Po’ Boy) and across the record he borrows or tweaks lines from literature as disparate and diverse as Shakespeare’s Othello, Henry Timrod’s Vision of Poesy, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic The Great Gatsby and Junichi Saga’s engrossing and fascinating Confessions of a Yakuza. He pulls Lewis Carroll’s Tweedledum and Tweedledee through the looking glass and into the album. Even the record’s title has been borrowed from a book (Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class by Eric Lott).

During High Water (For Charley Patton) Dylan incorporates the name and a line from an old British folk song into one of his lyrics, singing “the Cuckoo is a pretty bird, she warbles as she flies”. All of these sources, all of these references, are so deeply embedded in Dylan’s artistic makeup and embedded in the American folk tradition that he came out of.

He was performing Cuckoo Is A Pretty Bird all the way back in 1962, and here it was popping up in a line in one of his own songs 39 years later. It was not the first (and wouldn’t be the last) time that Dylan had drawn elements from a British folk song into his own new composition. He frequently used British and Irish folk melodies as the basis for his songs in the early 60s, and, much later, he built the 2012 song Scarlet Town around the traditional ballad Barbara Allen, a song he had performed 60 times in concert between 1962 and 1991. “This isn't British music. This is American music now, come on” is right.

Some people have criticised Dylan’s borrowings and references as thievery (the clue is in the album title) or even plagiarism, but writing for poetryfoundation.org, Robert Polito argues in favour of Dylan’s methods that “the scale and range of Dylan’s allusive textures are vital to an appreciation of what he’s after on his recent recordings”.

Of course, this is nothing new from Dylan. He has always absorbed and weaved together a wide range of cultural elements into his work; from the Bible to Bogart dialogue; from the Ancients to the Romantics and the Beats. Country tunes and civil war poetry. He brings together high art and low. He brings together influences from all over the world, from throughout all of time, and combines them with elements from all of American musical and cultural history, bringing the Old World and the New together, to create a rich, vivid and profound musical tapestry.

In Floater (Too Much to Ask), Dylan gives us the perfect image with which to describe his writing process, when he sings that his Grandmother could “sew new dresses out of old cloth”. This is exactly what he does so well on this album.

In the excellent and exhaustive book Let’s Do It: The Birth of Pop, Bob Stanley says that Bob Dylan “has maybe done more to unbottle the ghosts and magic of old-time music than anyone else in the rock era” (page 588), and nowhere else in his career does Dylan so consistently unbottle those ghosts and unleash that magic than in this trilogy of albums.

With its combination of influences, sources and references and its vital, free-flowing and exuberant, often down-right joyous music, “Love and Theft” is the soundtrack to the American dream; to the dream of America. It is one of the great pieces of American art. This album is On the Road come to life. It’s Aaron Copeland’s Hoedown via Elvis Aaron Presley’s hepcat swing. It rolls on like the Mississippi river and it’s as grand as the Appalachian Mountain range. It’s the heart of the Heartland and the soul of a nation before it was blown away. The echo of an America that doesn’t exist any more, can never exist again, and that you can’t get to any other way except for putting this record on and doing the darktown strut.

Elsewhere in 2001

Leonard Cohen released Ten New Songs, an album made up of ten new songs co-written, co-produced and co-performed with his longtime collaborator Sharon Robinson. His first album of original material since 1992’s The Future, and first since he returned from life in the Mount Baldy Zen Center, the album is as intimate as anything from Cohen’s career.

A Thousand Kisses Deep, Here It Is, By The Rivers Deep, You Have Loved Enough and Boogie Street are all pure poetry (indeed, as is so often the case with Cohen’s songs, some of these pieces either started out life as or later became poems, with many appearing in his 2006 collection Book of Longing). They are mysterious, and epic. Light and dark. They are panoramic and minuscule. They are nothing and they are everything.

The opening song, In My Secret Life, is as sensual, as full of longing, regret and passion as anything that Cohen ever wrote. In fact, it might be as sensual, full of longing, regret and passion as anything that anyone ever wrote.

I smile when I’m angry

I cheat and I lie

I do what I have to do

To get by

But I know what is wrong

And I know what is right

And I’d die for the truth

In my secret life

Cohen’s music is mystical. It can feel religious. His body of work is as deep as an ocean and runs like a mighty river. This is not his best, most realised or most complete album but it is still full of beauty, full of grace and it is deeply moving. In my secret life, I may sometimes hold him in slightly higher esteem and regard than I do even Bob Dylan.

While Dylan and Cohen were respectively releasing their 31st and 10th studio albums in 2001, The Strokes announced themselves on the international stage in a big way with their debut release, Is This It.

They’d formed as a band two years earlier and quickly worked up a buzz and reputation on New York’s live circuit. When they sent four tracks off to the newly formed Rough Trade Records in the UK, they can’t have known just how in demand they were about to become when those songs were released as an EP.

The Modern Age EP received rave reviews, as did their 16 date tour of the UK and Ireland that followed in support, and upon their return to the States they were hotly pursued by every major label, who all competed to out-bid each other to sign The Strokes. The band decided to go with RCA Records and released their incredible first album on July 30, 2001.

Even almost 25 years later this record is just as exciting as it was in 2001. It sounds as vital and liberating now as the first time you heard it, just as breathless and exhilarating. It still sounds fresher than any other rock release since.

Julian Casablancas’ voice is just as arresting and intoxicating now as then (it doesn’t matter that he drawls and slurs some words so much that even a quarter of a century later you’d be forgiven for still not knowing exactly what he’s singing); every riff and note from Albert Hammond Jr and Nick Valensi’s guitars are just as electrifying and thrilling, every bass line from Nikolai Fraiture is still as exciting and surprising and every crash on the drum from Fabrizio Moretti is still as urgent (and by the way, with names like those, of course they were destined to conquer the rock world).

Every track on the album is an anthem, a revitalising shock of life and energy. It’s a perfect whirlwind of unshackled, unbridled youth and freedom. It is a perfect guitar album. It is no wonder that they ushered in the re-birth of rock, and kick-started a million other garage bands to life. It is no wonder that Alex Turner just wanted to be a part of this band. It is no wonder that every executive in the industry wanted to sign this group, and release this record.

Every label in the music industry knew a good thing when they heard it in The Strokes, but even in the same year that the New York five piece had sparked an enormous bidding war for their services, one of the majors showed that the industry doesn’t always know exactly what it’s doing.

Howard Klein had signed Wilco to Warner Music subsidiary Reprise Records in 1994, but left the company following the group’s merger with AOL in 2001. Those still working at the label weren’t as sold on the Chicago alt-Country group and in June of the same year, Reprise A&R man Mio Vukovic rejected their groundbreaking new album on the basis that it wasn’t radio friendly enough.

Wilco offered their label $50,000 in exchange for the masters to their new album, and the label must have thought so little of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot that they let the band keep the rights for free.

After leaving the label, tracks from the album started to leak online. To combat the piracy but capitalise on the buzz that had begun to build around the record, Wilco uploaded it to their website in its entirety. It became so popular - of course it did, just listen to songs like I Am Trying to Break Your Heart, War on War, I’m the Man Who Loves You and the perfection of Jesus, Etc. - that it sparked yet another label bidding war.

After a lot of offers and negotiations, Wilco ended up signing with and releasing the album through Nonesuch Records, a subsidiary of none other than Warner Music Group.

Gillian Welch wrote the equal parts devastating and beautiful Everything Is Free when peer-to-peer file sharing sites like Napster were first on the rise. The song centres around the fear of losing your livelihood when the value of your labour, the value of your art, is stripped and chipped away. If the song was prescient at the time, then it seems down-right prophetic now.

We now live in a world where great art has been reduced to being seen as merely ‘content’. Where great artists are seen as replaceable by dodgy algorithms and computer coding. A world where those who hold the keys to the cultural kingdom - people like Daniel Ek, David Zaslav, Ted Sarandos and Bob Iger - have an open disdain and hostility for both real art and the real artists that create it. If something is free to make, then it is still too expensive for men like them.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek probably didn’t have Welch’s song in mind recently when he said that the cost of creating content is “close to zero”, but she already had the perfect rebuke for him

Cause everything is free now

That's what I said

No one's got to listen to

The words in my head

Someone hit the big score

But I figured it out

And I'm gonna do it anyway

Even if doesn't pay

Great art enriches your life in so many wonderful, unexpected and meaningful ways. People like Ek, Zaslav, Sarandos and Iger - who know the cost of everything and the value of nothing - should try engaging with some every now and then.

When I was little, my family would head down to a farm in Barnstaple, Devon each summer for a getaway.

It’s a long drive from London to the South West, and a long drive needs good music. To soundtrack the journey, my Grandad would make mix-tapes of his favourite songs, new and old, for us all to listen to on the drive there and back again. They became the soundtrack of our holidays, and even now in my head I refer to the songs that made up those mixtapes as Devon Songs. Lou Reed’s Perfect Day. Light and Day and It’s the Sun by The Polyphonic Spree. Do You Realize?? by The Flaming Lips. The stunning, life-affirming live version of I’m Your Puppet by Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham, from the absolutely perfect Moments From This Theatre album.

And the song that, for whatever reason, in my head is the Devon Song, The Dark is Rising by Mercury Rev.

This song was the first one I ever heard that made me realise just how big music can be. How all-encompassing it can feel. How much it can get inside you and paint a picture in your head. How important music can and should really be. That sense of scale and wonder has never gone away.

With those sweeping orchestral hits, the enormous strings and drums and the tiny voice; the undercurrent of piano and fleeting flutes and brass, the hope-filled and yet hope-less lyrics, this song surrounds you. The way it recedes and then crashes down on top of you, drags you under the current, the story it tells of dreams and of love? All the smoke, the snow, the stars and the streams. This is not just a song that soundtracks a holiday, but a song that soundtracks a life.

Notable Album Releases:

Björk - Verpertine

Daft Punk - Discovery

Kylie Minogue - Fever

Macy Gray - The Id

No Doubt - Rock Steady

Pulp - We Love Life

Ryan Adams - Gold

Sophie Ellis-Bextor - Read My Lips

Stereophonics - Just Enough Education to Perform

The White Stripes - White Blood Cells

Next Up: Tom Waits unleashes two albums on the same day, Norah Jones asks us to come away with her and Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots.

Of course. “Love and Theft” was released on 9/11/2001. I was working in radio and was on the air when the planes hit the towers. It was an oldies station, but all music stopped and we took calls from listeners for the rest of the morning.

After an intense day on the air, when I finally got a break, I rushed to the local record store because I knew two albums were going to be released that day: the new Dylan and the new John Hiatt. Dylan’s album title was pored over by many - myself included - as prescient to the day’s events. The same came be said of Hiatt’s “The Tiki Bar is Open”, though, which seemed to offer the perfect solace as escape from this hellscape of circumstances, at least for a little while.

Great piece! And, to be frank, I lean more toward this one than Time Out of Mind. But the whole trilogy is truly classic Dylan in every way.

Wonderful work, Matthew! You capture so well what makes L&T such a shining gem in Dylan's treasure chest. Like your other commenters, when anyone mentions 2001 my mind instantly goes back to 9/11. Thanks for reminding us that it was also an amazing year for music. I still listen regularly to those Gillian Welch and Wilco albums, and Ryan Adams's Gold, too. Damn near perfect records. Impressive Devon playlists, too! Sounds like you were shaped by great music from the start, Matthew.