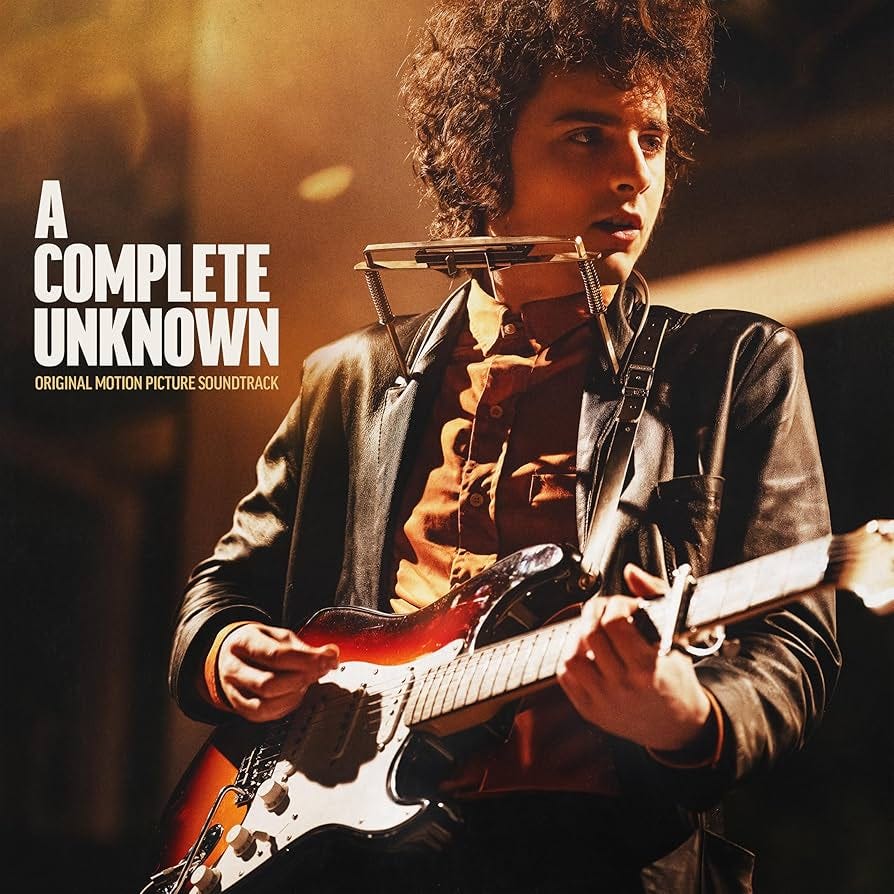

2025: A Complete Unknown

"I don't think they want to hear what I want to play"

James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown could well open with an epigraph lifted directly from the first sentence of Kurt Vonnegut Jr’s 1969 opus Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death: “All this happened, more or less.”

It could also close with a quote from a more contemporary satirist, Stewart Lee: “Now, none of that was true. But I feel like what it tells us is true.”

Equally, an audience could be forgiven for thinking, or saying, “I don’t believe you, you’re a liar” to this film as the credits roll.

There are already plenty of reviews and articles that go into detail on the accuracies and inaccuracies in A Complete Unknown, but I’m not sure that all of them matter that much; whether it’s important if Dylan did or said certain things at a certain point or whether he ever shared a Bugle with Johnny Cash or a bed with Albert Grossman. The film is more of an amalgamation of historic happenings which pull together several key moments from the era into a more movie-friendly, condensed narrative, rather than a retelling of events exactly as they happened. It’s trying to get to the core of the conflict between Dylan and the folk movement, rather than simply list the facts and do so all in order, like any number of the countless books already available about the man do (one of which is Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties, which this movie is loosely based on). And anyway, there is a huge element of creative licence that can be allowed in a film about Bob Dylan considering the huge amount of creative licence the real life Bob Dylan has taken throughout the long, strange time he’s spent telling us his story.

And for the most part in the film, that’s fine. Where it can be jarring, though, is when that creative licence rubs up against the reality of people not named Bob Dylan, and most notably in the portrayals of all of the women in the film.

Monica Barbarro does an incredible job in capturing the intonation and inflection of Joan Baez’s talking voice (not so much in her singularly impressive soprano singing voice, although Barbarro does demonstrate some fantastic singing of her own) but the character is reduced to little more than a one-dimensional love interest rather than the fierce, funny, multi-faceted, famous and inspiring woman that she really is and always has been. Similarly, the real Suze Rotolo has been moulded into the fictional Sylvie Russo, and, in the process, has had all the interesting parts of her personality shaved off; her courage and strength, her radical, progressive and powerful political drive, her humour and her humanity have all been whittled away so that she is shown to be not much more than a simpering, doe eyed dame waiting for Dylan’s next spark of genius to light up her life. And if those felt like entirely reductive portraits of these interesting women, then you should read this Substack from Merrill Markoe about the contrast between the real life and the movie versions of Toshi Seeger.

Curiously, another character who feels misplayed and almost hollowed out of all that is interesting about their real life counterpart is Bob Dylan himself. In contrast with how brilliantly the Pete Seeger character is fleshed out and portrayed - faultlessly, by Ed Norton, who radiates eternal warmth and real conflict and who is a joy to watch whenever he’s on screen, and who is easily the beating emotional heart of this movie - Dylan himself is played pretty narrow, pretty much straight down the line and pretty much one-notedly and one-dimensionally by Timothée Chalamet.

He has no character arc. He has no depth and he has no sense of motivation. He turns up in New York already in slick talking, untouchably cool 1965 mode and is played with none of the warmth, charisma, empathy, magnetism, humanity or good humour that the real life Dylan displayed all throughout his young years. As such, there is no real sense of progression or development by the character from his arrival on the scene and on the screen as a complete unknown to his going electric at the climax of the film; there is no real sense of purpose or drive in his character which informs his actions or lets us know why he does everything he does. There is no sense of internal, or really for that matter, external struggle. He always just is. He’s doing everything he does just because that’s what has to happen next, not because that is what his character feels compelled to do. You don’t feel pulled along with him as he battles with his direction or decides what road to walk down. He’s not empathetic, he’s not warm, he’s not human, he’s not charismatic or funny, and, without all of that, he’s not really very interesting, either.

Occasionally, Chalamet stops being Timothée Chalamet just long enough to approach becoming Bob Dylan but for the most part, he doesn’t fully capture the essence of the man or the character he’s playing. Admittadely, it’s hard to capture the undefinable magic of someone so mercurial, so magnetic and un-knowable, and, though there are flickers of Dylan here and there, for the most part Chalamet feels like an actor playing a role or a man doing an impression far more than he ever allows you to feel like you’re watching the real deal. Dylan is an unparalleled one-off cultural figure, but so was Elvis Presley, and even though Austin Butler never completely looked or sounded exactly like The King, his portrayal in Baz Luhrmann’s 2022 biopic got to the heart and to the core of the character in a way that Chalamet never really gets close to here. He never quite gets hold of the mysterious magic that makes Bob Dylan such a fascinating figure in the first place, in the way that Jamie Foxx did as Ray Charles way back when, or in the way that Viola Davis played Ma Rainey more recently.

And to compare it to a more contemporaneous (non-biopic) performance, one that is also still in cinemas, Chalamet fades into his role as Bob Dylan far less than Ariana Grande manages to keep herself out of her performance of - and where she truly becomes, truly embodies - Glinda, in Wicked. Chalamet and Grande are both pop stars, really. They’re both about as big as you can get in your respective field without being the absolute biggest name, but only one of them manages to completely cast aside their own tall shadow and portray the character of someone else in their recent films (Grande is not the only excellent part of Wicked, either, which is a surprisingly brilliant, moving, empathetic and enjoyable film, but her phenomenal vocals throughout - alongside those of Cynthia Erivo - are especially breath-taking and show-stealing).

Back in 2018, Twitter user @BrandyLJensen wrote that "some people just can’t be believably cast in a period piece like sorry Jessica Biel you have a face that knows about text messaging". A couple of years later, a Tumblr post made a similar point, that “Ben Affleck is one of those people who just cannot work period dramas at all. He has a face that knows about emails”. This kind of online observation has more recently been condensed into the phrase “iPhone face”, which is used to make the same point about actors who have faces which have clearly seen an iPhone in their time. Everybody in this movie, except for maybe Pete and Toshi Seeger, looks like they have seen and used an iPhone, from Bob Dylan to the adoring audiences who look at him, starry eye’d and laughing, as his career or his cars speed away from them. But as well as that, I would argue that almost everybody in this movie, except again for Ed Norton’s Pete Seeger (as well as Johnny Cash and Jesse Moffette), also has iPhone voice.

The music in the movie is, on the whole, fantastic. Chalamet has perfected Dylan’s idiosyncratic harmonica playing, and sometimes even outplays his real life counterpart. The richness and fullness of the sound that the band makes at the dramatic Newport finale is even richer, fuller and warmer than the sound the real life backing group achieved. But Chalamet sings like a Dylan disciple, not like Dylan himself. He sings like someone who knows what a voice note is. He sings like someone who has heard of Pro Tools or fooled around on Garage Band and used after effects or auto-tune before. He sings like someone who has picked up a guitar fifty years after Dylan’s impact first sent shockwaves through the musical world, rather than like someone who was honestly, naturally, unstoppably and ultimately, accidentally, sending those shockwaves himself.

The three times his music, and subsequently his whole performance, was most effective, and effecting, were when he quietly sings the opening verses of Girl From the North Country at the Seeger breakfast table (“Well, that’s all I got so far.” “It’s a good start!”), when he plays The Times They Are a-Changin’ at Newport and the crowd spontaneously erupt, join in, celebrate and rejoice (a genuinely spine tingling moment and the closest the film ever gets to portraying the electrifying effect Dylan has and had on people) and at the excellent Newport ‘65 finale. Though, notably, most of the impact in these performances came from the way that the music itself was shown to impact people - from the stunned silence of the Seeger children, to the euphoric rejoicing of the Newport crowd and then ultimately their furious response to the electric set - rather than from the actual performances themselves.

If this all makes it sound like I didn’t enjoy this movie, then I would like to add that I did. I liked the movie when it was on, but I didn’t love it. It’s completely fine. It’s Ok and it’s alright, and at times, it’s even pretty good and all the rest of it, but it could have been great and it is so frustrating that it’s not. It all feels too rote and bland and perfunctory and superficial and Dylan has never been any of those things. It feels like a biopic by the numbers and Dylan has never done anything by the numbers. At no point did the film threaten to come close to the quality or excitement or to capture the magic of the real life footage and artefacts of the real life Dylan that we have from this time. Quite often, it just made me wish I was simply watching Dont Look Back or No Direction Home, instead. In fact, the first thing I did when I got home from the cinema was to watch The Other Side of the Mirror to get a refreshing dose of the real Dylan performing at the real Newport Folk Festival. He had so much warmth, charisma, personality, charm, energy, humour and expressiveness at those shows which is completely untouched and unexplored, unrepresented and unshown in the film. In the film, he is spiky and rude and unlikable and often just a blank void of pseudo-personality. It’s no wonder that Joan Baez says he’s “kind of an asshole” early on, but a real wonder that no one else can seem to see it.

Around Dylan/Chalamet, though, the supporting cast all play their roles much better, and with much more interest. Ed Norton is the pick of the bunch as Pete Seeger, and deserves all the plaudits he’s getting, whilst Eriko Hatsune is given barely anything to work with as his wife Toshi. Nevertheless, she still manages to make herself a presence whenever she is present on screen. Similarly, Monica Barbarro is excellent with what she is given to do as Joan Baez, which a not-very believable or interesting writing of her character but a strong, vivid and powerful performance anyway (there is an undeniable chemistry between Barbarro and Chalamet in the fictitious Newport ‘65 duets, something it would have been nice to see more of). Dan Fogler felt like he put a little too much of his Jacob Kowalski character from Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them into his portrayal of Albert Grossman, but is enjoyable to watch him have fun with the role nonetheless whenever he’s in a scene. Scoot McNairy plays the almost completely non-verbal Woody Guthrie character note-perfectly, and is full of touching heart and fighting spirit, and brings some all-too-rare genuine emotion and pathos to the film, whilst Boyd Holbrook brings a weighty swagger to the larger-than-life Johnny Cash and delivers some of the all-too-rare genuinely funny moments in the film (Dylan is a seriously funny guy and so were the people he had around him, but there are maybe only four or five laughs to be had in this whole movie).

Among my favourite scenes were those where Chalamet took a backseat and his co-stars took centre stage. When Dylan and Jesse Moffette - played brilliantly by Muddy Waters’ son(!) Big Bill Morganfield - trade licks and sing some blues together on Pete Seeger’s educational public access television show (and which subtly demonstrates that Dylan had equal roots in the blues as in the folk movements, and was more accepted by the black blues community for who he was, rather than by the white folk crowd who wanted to cow and control him and make him their messenger), and later on when Seeger tries to explain to Dylan why it’s so important that he play the old songs at the ‘65 Newport festival. This is one of the few times the film manages to balance the pathos of age and wisdom, the importance of the moment, and the sardonic humour and unstoppable energy and righteousness of youth.

If more of the film could have captured the magic in the dynamics rippling underneath these two scenes, it would have been a far better picture.

Outside of my family, Bob Dylan has been the most important man in my life. He has been a friend of mine and a teacher, a guide and a companion. Thanks to him, I have listened to musicians and singers that I may never otherwise have encountered. I have read books that I might never otherwise have heard of and watched films that I might never otherwise have picked for myself (and off the back of its important depiction in A Complete Unknown, I am now looking forward to watching Now, Voyager, starring Bette Davis and Paul Henreid). Thanks to Dylan, I have travelled the world and been to places I might never otherwise have been, and seen places that I may never see again, following his Never Ending, Outlaw and Rough and Rowdy Ways tours over the last fourteen years, around Europe, Asia and America.

Like many others, I love the idea that this new movie might be a new entry point into the world of Bob Dylan for some people; and the idea that they will be about to embark on their own journeys with him. Some of the greatest moments of my life have been soundtracked by Bob Dylan’s music, and some of the hardest times have been eased and softened by his company. I hope this can be the start of a wonderful friendship between Dylan and a wave of new fans, too, and that they can experience all of the same magic, wonder, awe and astonishment as I have.

I hope that for anyone unfamiliar with his work that this movie makes them want to get more familiar with it. Makes them want to go back and spend some time with the real footage, and to appreciate the real genius of his songs, and his real performances in The Other Side of the Mirror, Dont Look Back and No Direction Home. They’re a lot better than, a lot more interesting to look at, and reveal a lot more about the man himself, than A Complete Unknown. But that’s no surprise, the real Bob Dylan is better than just about anything, and that alone still makes A Complete Unknown worth a watch.

And so, while you can - and if you can - go watch A Complete Unknown in the cinema. Don’t just wait for the physical release. The environment and the atmosphere and the screen and the sound and the event of being in the cinema make key scenes with Woody Guthrie in the hospital more moving, makes the Newport crowd response (both positive in ‘64 and negative a year later) more dramatic, affecting and powerful and the chemistry between Cash or Baez and Dylan more electrifying. The magic of the moment also makes all the inaccuracies more palatable and forgivable.

Bob Dylan is an artist that is best experienced live in concert, who does his best work in live performance, and similarly, the best way to experience A Complete Unknown is surely in its own live environment, with a live audience around you responding to everything in the moment. But don’t take it from me, go see this movie for yourself. You shouldn't let other people get your kicks for you.

Further Reading…

Head on over to The Mixtape for another, far better, review of A Complete Unknown from our friend Michael Elliot.

And in case you missed the hyperlink in the main text, here is that Toshi Seeger piece from Merrill Markoe at Still Looking for the Joke again, which really is a fascinating read.

And finally, from outside of the Substack eco-system, this hilarious piece about The Bugle scene by Jill Mapes at Hearing Things.

If you enjoy my work, you can support it below. Thanks for reading!

The movie seems like Dylan himself: nonconformist, going its own way...

Fantastic article, you had me at Stewart Lee!!!