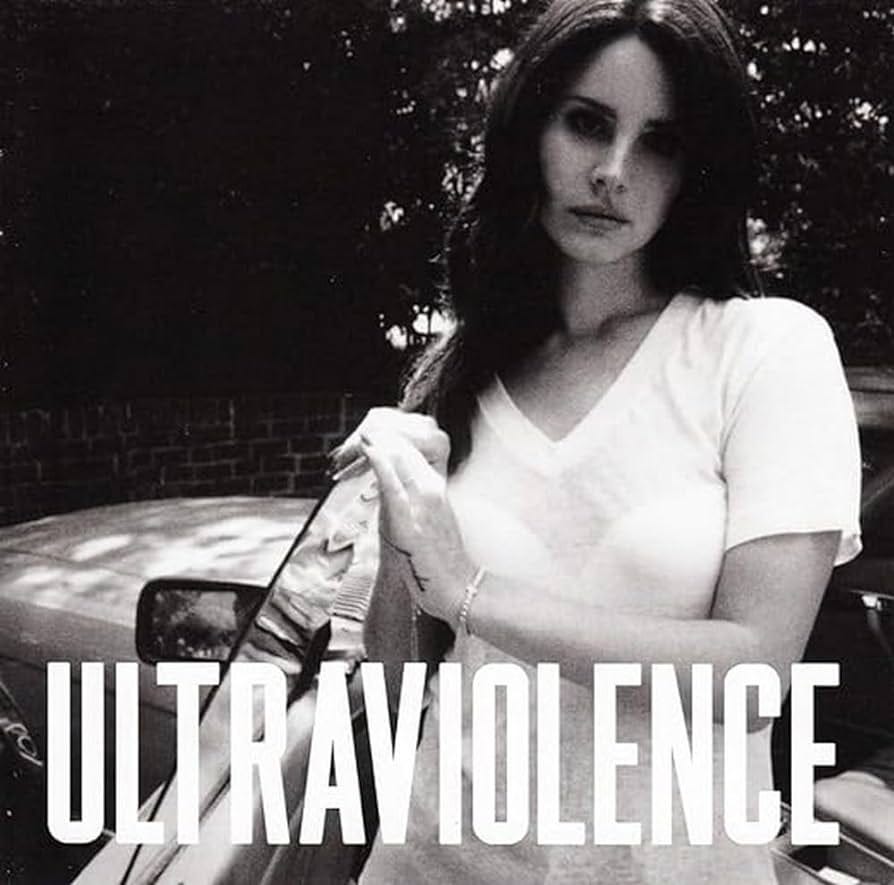

2014: Ultraviolence - Lana Del Rey

Looking back at 30 years of music | Lana Del Rey, Future Islands, Alvvays, Mac DeMarco, Taylor Swift, Leonard Cohen, Adam Cohen

Writing about Lana Del Rey’s then-latest release for Pitchfork in 2014, Mark Richardson assessed that “the first section of the album is so gorgeous and rich, Ultraviolence at first seems better than it is” but let’s be honest, if this album seems good when you listen to it, that’s because it is.

Actually, I don’t think this is just a good album, but Lana Del Rey’s first really great one, and certainly a record that stands out on its own in her discography.

A lot of this is down to the sound and the feel of the album, which was provided by producer Dan Auerbach from The Black Keys. That’s not to take the credit away from Lana Del Rey here and explain away that the raised quality of the record is due to the man that she worked with on it - her writing on this album is as good as anything in her career, and in many places, better than it ever would be again - but the real formula for success is in the convolution of her writing and his production.

Del Rey has a knack for pulling off lines which would never work coming out of someone else’s mouth - perhaps the fact that Lana Del Rey herself is a character for Lizzie Grant to project on to and through helps with this - but she also has a way of coming up with turns of phrase which are laughably good; musical, artistic, literary and poetic all at once. So often it takes her just one phrase to paint a masterpiece; make a movie or fill out a whole novel’s worth of overwhelmingly vivid imagery where others would struggle to evoke such a scene with a whole song-full of lyrics.

What sets this album apart from her other great releases is the regularity with which she churns out such phrases. She is almost showing off with her writing on this record, and, combined with her laconic, quietly confident and almost detached and indifferent delivery, you’re left with a collection of über-cool performances which feel like Del Rey was hardly even trying and yet still managing to sound this good.

Since her first album, Lana Del Rey has written songs that allude to relationships and physical encounters with older men. Men who want to impress and regale her with their maturity and superior intellect or their love of obscure beatnik poetry and jazz musicians; men who want to control her sexually, to control her sexuality or autonomy and who don’t like to be told “no”. Men who have some kind of power over her, or at least, men wished they did. And, since her first album, Del Rey has drawn comparisons - both in her own writing and in writing about her - to Vladimir Nabokov’s legendary 1955 novel, and character, Lolita.

In her recent book Monsters: What Do We Do With Great Art By Bad People?, Claire Dederer argues that one of the most upsetting aspects of Nabokov’s Lolita is the almost total absence of the titular character throughout the story. Once she has been spirited away by Humbert Humbert, we remain inside his head and see her through his eyes only; through his lens as his wicked lust devalues, diminishes and disappears her personhood, and her childhood.

We never see the world through Lolita's eyes. We never know what she is thinking or what she is feeling or what she is hoping will happen. We never get a sense of her personality or autonomous nature. In essence, we never experience her as a human being herself, only as the prepubescent object of Humbert Humbert’s desire.

Whilst on Ultraviolence, Lana Del Rey doesn’t make any direct allusions to Lolita, as she did on her debut Born to Die, plenty of the songs and lyrics can be seen as giving voices to characters like Lolita. To women who have been abused, suffered and been mistreated; who have been led astray, taken advantage of or manhandled.

But, crucially, she is no child and neither are any of the characters in these songs. On Ultraviolence, she is Lolita all grown up.

All of the women in these songs have been damaged and abused but made it through to the other side and, in their way, have used their powerlessness to gain some sort of power in their positions. They may not always come out on top, but they are all now in command of their destruction and destructive behaviours. Maybe, at times on this album, Del Rey has become another kind of monster in facilitating that, herself.

He used to call me DN

That stood for deadly nightshade

'Cause I was filled with poison

But blessed with beauty and rage

Jim told me that

He hit me and it felt like a kiss

Jim brought me back

Reminded me of when we were kids

If you combine everything that Lana Del Rey is doing lyrically and vocally on the album with Dan Auerbach’s carefully crafted and structured sonic landscape, you end up with a masterpiece that doesn’t sound like anything else in her catalogue, or indeed, like any other releases this side of the 21st century.

Hazy, atmospheric - almost ethereal and superlunary - this album feels like it’s coming through to you from some far-off and liminal space; from some broken down radio, or through the wall of the dive-bar music venue next door. You can never pin it down, you’re never right on the beat or in the line of fire. You’re just a bystander as the stories pass you by. Wash over you and drift overhead. Del Rey’s voice - often multi-layered and drenched in reverb - drifts along beside and through you like an enchantment on its lazy way someplace else.

There are tempered strings throughout the record; tempered with piano countermelodies and synths and studio effects. Hypnotic guitars abound across the album. The drumming on every track is phenomenal and is the quiet, beating heart of all the instrumentation. The music lurches and creeps. It builds and beguiles. It grows on you like poison ivy; climbing across, around, over and into you.

This is not the sort of record that will age or date badly; it sits outside of any one musical time. The lives of the characters within it are intensely modern in their language and their positions, and yet the literary and musical reference points in the writing are far from it (the title of the album alone draws connections straight away to Anthony Burgess’ infamous A Clockwork Orange, whilst she also references Hemingway in Money Power Glory, Lou Reed in Brooklyn Baby and others across the album). The music also flits between the present and the past. With enough musical touch-points from the late 60s and early 70s West Coast scene, and contemporary flourishes and touches, this record sounds like a soundtrack for the modern day lounge lizard.

Following her first album, and especially after her infamous performance of Video Games on SNL in 2012, there was a lot of doubt online and in the press about Lana Del Rey’s ability to sing - doubts that should be allayed by the vocal performances throughout Ultraviolence, but especially on songs like Shades of Cool or Sad Girl.

Sam Cooke once said that “voices ought not to be measured by how pretty they are. Instead they matter only if they convince you that they are telling the truth”. Not only was Del Rey’s vocal ability called into doubt following that first release, but also the authenticity of the character she uses to write her songs.

I’d defy anyone to listen to the version of Jessie Mae Robinson’s The Other Woman which closes this record and still question either Lana Del Rey’s vocal ability or her authenticity as an artist, and her ability to convey the truth when she is singing.

Elsewhere in 2014…

Samuel T. Herring danced his way into countless hearts when performing tracks from the synth-pop Future Islands breakout album Singles, which is bookended by two of their best songs in Seasons (Waiting on You) and A Dream of You and Me.

Also releasing albums with career defining tracks on them were Alvvays - their eponymous debut featuring their most famous song (with good reason), Archie, Marry Me - and Mac DeMarco whose sleaze-rock Salad Days features his best track, Let Her Go.

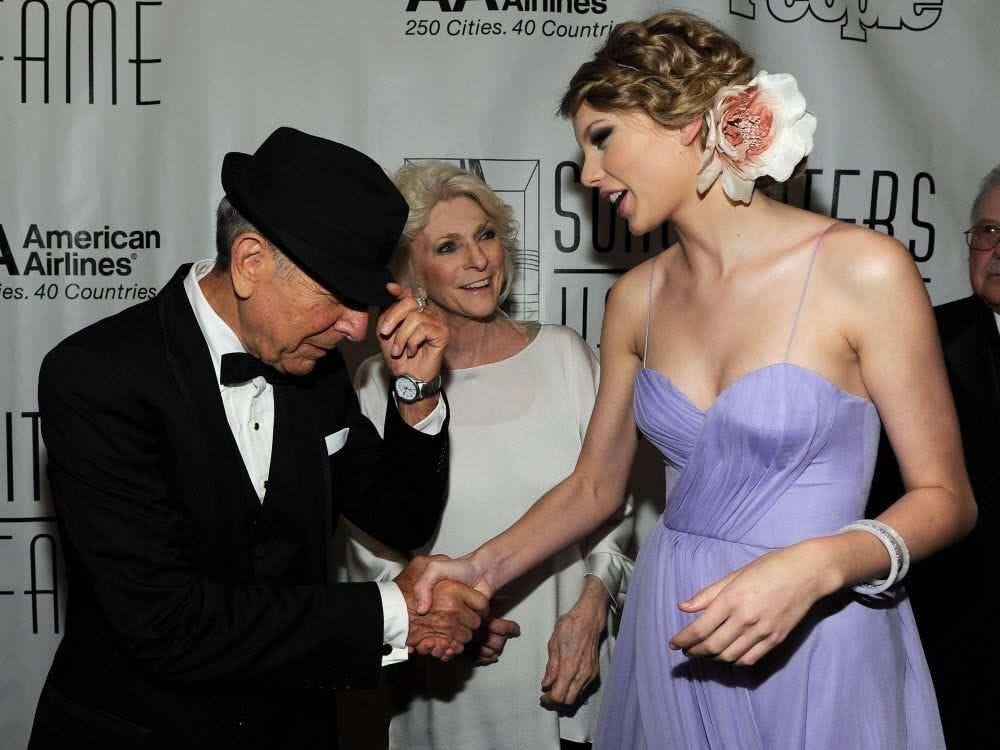

Taylor Swift took another step towards world domination with the release of 1989, her first all-pop album, which contained monster hits like Shake It Off, Style, Bad Blood and Out of the Woods whilst at the other end of his career, Leonard Cohen returned with the follow up to 2012’s Old Ideas, Popular Problems.

Before Old Ideas he hadn’t released a studio album in ten years, but the now-prolific octogenarian was back with a great collection of songs including Slow, Almost Like the Blues and Did I Ever Love You.

We’ll be hearing from him again baby, long after he’s gone, in a couple of weeks time, when we get to 2016 and the phenomenal, You Want It Darker.

Back in 2014, though, and Leonard wasn’t the only Cohen with a new album out, either. His son, Adam, released his fourth record, We Go Home, of which the title track is a clear standout and another career highlight single released in this year.

Notable album releases

alt-J - This is All Yours

Ariana Grande - My Everything

Beck - Morning Phase

The Black Keys - Turn Blue

Coldplay - Ghost Stories

Charli XCX - Sucker

FKA Twigs - LP1

Run the Jewels - Run the Jewels 2

Sharon Van Etten - Are We There

The War on Drugs - Lost in the Dream

Up next: Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit

Wonderful writing here, Matthew. I especially like your take on Lana Del Rey as a grown-up Lolita. One of my favorite plays from the 30-year span you're covering is How I Learned to Drive. The playwright Paula Vogel has spoken about her play in precisely those terms, taking a scenario akin to Nabokov's Lolita and telling it from the girl's perspective, or rather the perspective of the woman the girl later became. That's a revelatory way of viewing Ultraviolence--thanks Matthew!